Home >Web Front-end >JS Tutorial >Detailed explanation of if and switch, == and === in javascript_javascript skills

Detailed explanation of if and switch, == and === in javascript_javascript skills

- WBOYWBOYWBOYWBOYWBOYWBOYWBOYWBOYWBOYWBOYWBOYWBOYWBOriginal

- 2016-05-16 15:48:211115browse

When I changed the plug-in BoxScroll today, because there were more than two conditional judgments in the if, I immediately thought of rewriting the switch. Halfway through the change, I suddenly remembered a requirement in code quality detection tools such as JSHint. Use === to replace == instead of unreliable forced transformation. Then I suddenly wondered, would changing to switch reduce efficiency? Is the actual judgment in switch == or ===?

When you have an idea, quickly pick up a chestnut and eat it in one bite:

var a = '5';

switch (a) {

case 5:

console.log('==');

break;

case "5":

console.log('===');

break;

default:

}

The final console display is ===, which seems to be safe to use. I looked up my previous study notes. Well, in the third year of high school, it was indeed said that the switch judgment is a congruence operator, so no type conversion will occur. Here’s a summary

1.if and switch

if is the most commonly used, there isn’t much to say. One thing worth noting is: if is actually very similar to ||. If conditionA in if (conditionA){} else {} is true, then it will not even look at the code in else after executing the code block before else. . Just like when || is true in the front, it will be ignored later, even if there are many errors in it. Based on this property, of course, put the code blocks that may be used most in front to reduce the number of judgments. On the other hand, if there are many if judgments and the number of possible executions is relatively evenly distributed, then subsequent judgment statements will have to execute the previous judgments one by one each time, which is not conducive to optimization. A better approach is to change one-level judgment statements into two-level judgment statements, such as

if (a > 0 && a <= 1) {

//do something

} else if (a > 1 && a <= 2) {

} else if (a > 2 && a <= 3) {

} else if (a > 3 && a <= 4) {

} else if (a > 4 && a <= 5) {

} else if (a > 5 && a <= 6) {

}...

changes to

if (a > 0 && a <= 4) {

if (a <= 1) {

//do something

} else if (a > 1 && a <= 2) {

} else if (a > 2 && a <= 3) {

} else if (a > 3 && a <= 4) {

}

} else if (a > 4 && a <= 8) {

//

}..

Although each of the previous judgments has been added one more time, the subsequent judgments have been reduced by (4-1)*n times, which is still a full profit. Suddenly I feel that this method is a bit similar to nested loops. Putting the loops outside with a small number of loops can help optimize performance. How to divide it into two or even multiple layers depends on the specific situation.

Switch is if’s closest comrade. Every time if is too busy, he comes to help. There is probably nothing to say about the mutual conversion between switch and if, and switch, like if, executes judgments sequentially from top to bottom. The difference is that the else in if does not work in switch. It has its own little brother: break . If no break is encountered, switch will continue to execute, such as

var a = 2;

switch (a) {

case 1:

console.log("1");

//break miss

case 2:

console.log("2");

case 3:

console.log("3");

default:

console.log('no break');

}

Finally the console displays 2,3,no break. In fact, it is quite easy to understand. break prompts the program to jump out of the internal execution body and go to the next case judgment. If there is no more, it is equivalent to if(condition){A}{B}. Without else, of course both A and B will be executed. There are two more tips. One is that you can write any expression in switch and case, such as

switch (A + B) {

case a * b:

console.log("1");

break;

case a / b + c:

break;

//...

default:

console.log('no break');

}

The actual comparison is (A B)===(a*b) and (A B)===(a/b c). Second, switch has a special usage, such as

switch (true) {

case condition1:

//do something

break;

case condition2:

break;

//...

default:

//..

;

}

At this time, each case in the switch will be judged and executed in order. As for switch(false)? It’s useless.

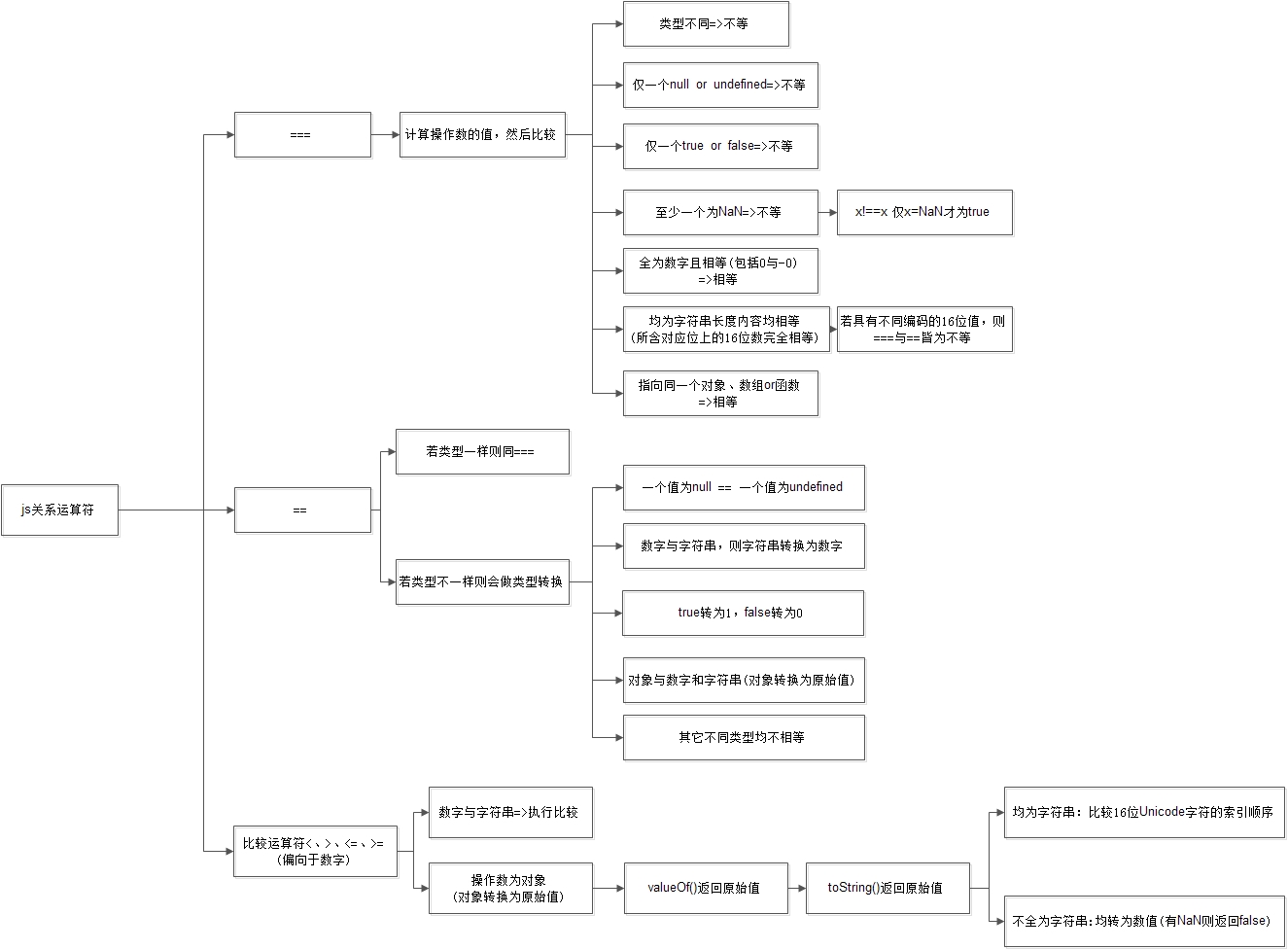

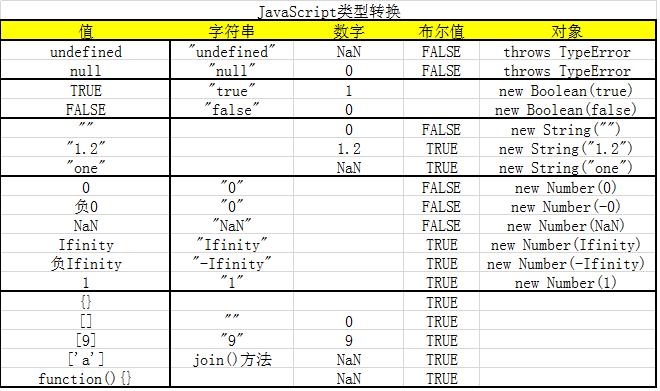

2.== and ===

In one sentence, the congruence and inequality operators are no different from the equality and inequality operators, except that the operands are not converted before comparison.

The most classic case

var a = "5", b = 5; a == b //true a === b //false var a = "ABC", b = "AB" + "C"; a === b //true

The reason why the following shows true is actually inseparable from the immutability of the string type. On the surface, it seems that b is just concatenating a string, but in fact it has nothing to do with the original b. Each string is stored in a specific place in the memory pool. When b="AB" "C" is executed, strings AB and C have been destroyed, and b points to the location of ABC in the memory pool. Since the string ABC was found in the memory pool before pointing (because a refers to it, it exists), so b points to the same area as a, and the congruence judgment is equal. If there is no variable before b pointing to the string ABC, then there is no variable in the memory pool, and a space will be allocated for ABC in it, and b will point to ABC.

Attached are two previous summary pictures:

The above is the entire content of this article, I hope you all like it.

Related articles

See more- An in-depth analysis of the Bootstrap list group component

- Detailed explanation of JavaScript function currying

- Complete example of JS password generation and strength detection (with demo source code download)

- Angularjs integrates WeChat UI (weui)

- How to quickly switch between Traditional Chinese and Simplified Chinese with JavaScript and the trick for websites to support switching between Simplified and Traditional Chinese_javascript skills