Technology peripherals

Technology peripherals AI

AI General artificial intelligence, artificial intelligence perception, and large language models

General artificial intelligence, artificial intelligence perception, and large language modelsGeneral artificial intelligence, artificial intelligence perception, and large language models

Perhaps you haven’t noticed that the recent performance of artificial intelligence systems has become more and more surprising.

For example, OpenAI’s new model DALL-E 2 can generate engaging original images based on simple text prompts. Models like DALL-E make it harder to deny the notion that artificial intelligence can be creative. Consider, for example, DALL-E's imaginative take on "a hip-hop cow wearing a denim jacket recording a hit single in the studio." Or for a more abstract example, check out DALL-E's explanation of the old Peter Thiel line "We want flying cars, not 140 characters."

Meanwhile, DeepMind recently announced a new technology called Gato's new model, which can single-handedly perform hundreds of different tasks, from playing video games to having conversations to stacking real-world blocks with a robotic arm. Almost all previous AI models were able to do one thing and one thing only—for example, play chess. As such, Gato represents an important step toward broader, more flexible machine intelligence.

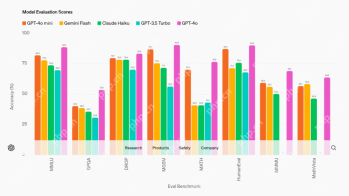

And today’s large language models (LLMs)—from OpenAI’s GPT-3 to Google’s PaLM to Facebook’s OPT—have a dizzying array of language capabilities. They can have nuanced and in-depth conversations about almost any topic. They can generate impressive, original content themselves, from business memos to poetry. To give just one recent example, GPT-3 recently authored a well-written academic paper about itself and is currently undergoing peer review for publication in a prestigious scientific journal.

These advances have inspired bold speculations and heated discussions in the artificial intelligence community about the direction of technological development.

Some credible AI researchers believe we are now very close to “artificial general intelligence” (AGI), an oft-discussed benchmark that refers to powerful, flexible artificial intelligence that can operate on any Outperforming humans in cognitive tasks. Last month, a Google engineer named Blake Lemoine made headlines by dramatically claiming that Google's large-scale language model, LaMDA, is sentient.

Resistance to such claims has been equally strong, with many AI commentators dismissing the possibility out of hand.

So, what are we to make of all the amazing recent advances in artificial intelligence? How should we think about concepts like artificial intelligence and artificial intelligence perception?

Public discourse on these topics needs to be reframed in several important ways. Over-excited enthusiasts who believe that superintelligent AI is just around the corner, and dismissive skeptics who believe that recent developments in AI are just hype, are both off the mark in their thinking about some fundamental aspects of modern AI.

AI is an incoherent concept

A basic principle about artificial intelligence that is often overlooked is that artificial intelligence is fundamentally different from human intelligence.

It is a mistake to compare artificial intelligence to human intelligence too directly. Today’s artificial intelligence is more than just a “less evolved” form of human intelligence. Tomorrow’s super-advanced AI won’t just be a more powerful version of human intelligence, either.

Many different intelligence modes and dimensions are possible. Artificial intelligence is best thought of not as an imperfect imitation of human intelligence, but as a unique, alien form of intelligence whose contours and capabilities differ from ours in fundamental ways.

To make this more concrete, briefly consider the state of artificial intelligence today. Today’s artificial intelligence far exceeds human capabilities in some areas – while falling far behind in others.

For example: For half a century, the "protein folding problem" has been a major challenge in the field of biology. In short, the protein folding problem requires predicting the three-dimensional shape of a protein based on its one-dimensional amino acid sequence. Decades and generations of the world's brightest minds have worked together to fail to solve this challenge. One reviewer in 2007 described it as "one of the most important yet unsolved problems in modern science."

At the end of 2020, an AI model from DeepMind called AlphaFold provided a solution to the protein folding problem. As John Moult, who has been engaged in protein research for a long time, said, "This is the first time in history that serious scientific problems have been solved by AI."

Solving the mystery of protein folding requires spatial understanding and high-dimensional reasoning forms, and this It is simply beyond the grasp of human thinking. But it’s not beyond the grasp of modern machine learning systems.

Meanwhile, any healthy human child possesses “embodied intelligence” that far exceeds that of the world’s most sophisticated artificial intelligence.

From a young age, humans can effortlessly do things like play catch, walk across unfamiliar terrain, or open the kitchen refrigerator for a snack. It turns out that these physical abilities are difficult for artificial intelligence to master.

This is encapsulated in the "Moravec Paradox". As AI researcher Hans Moravec said in the 1980s: “It is relatively easy to get a computer to perform at an adult level on an intelligence test or to play chess, but it is difficult or impossible to get a computer to perform at the level of a one-year-old child. .Perception and mobility."

Moravec's explanation for this unintuitive fact is evolutionary: "Encoded over a billion years in the large, highly evolved sensory and motor parts of the human brain Experience about the nature of the world and how to live in it. [On the other hand,] the thoughtful process we call higher reasoning is, I believe, the thinnest layer of the human mind, and it works only because It is underpinned by this older, more powerful, albeit often unconscious, sensorimotor knowledge. We are all outstanding Olympians in the realms of perception and movement, so good that we make the difficult look easy.”

To this day, robots still struggle with basic physical abilities. Just a few weeks ago, a team of DeepMind researchers wrote in a new paper: "Current AI systems' understanding of 'intuitive physics' pales in comparison to that of very young children."

What is the result of all this?

There is no such thing as general artificial intelligence.

AGI is neither possible nor possible. Rather, it is incoherent as a concept.

Intelligence is not a single, well-defined, generalizable ability, or even a specific set of abilities. At the highest level, intelligent behavior is simply an agent acquiring and using knowledge about its environment to pursue its goals. Because there are a large (theoretically infinite) number of different types of agents, environments, and goals, intelligence can manifest itself in countless different ways.

AI guru Yann LeCun summed it up well: "There is no such thing as general artificial intelligence...even humans are specialized."

Convert "general" or "true" artificial intelligence Defining AI as something that can do what humans can do (but better)—thinking human intelligence is general intelligence—is short-sighted and human-centered. If we regard human intelligence as the ultimate anchor and standard for the development of artificial intelligence, we will miss all the powerful, profound, unexpected, socially beneficial, and completely non-human capabilities that machine intelligence may have.

Imagine an AI that had an atomic-level understanding of the composition of Earth’s atmosphere and could dynamically predict with extremely high accuracy how the entire system would evolve over time. Imagine if it could be designed to engineer a precise, safe geoengineering intervention in which we deposit certain amounts of certain compounds in certain places in the atmosphere, thus counteracting the greenhouse effect caused by humanity's continued carbon emissions, mitigating global change. Effects of warming on the Earth's surface.

Imagine an artificial intelligence that can understand every biological and chemical mechanism in the human body down to the molecular level. Imagine if it could thus prescribe a diet tailored to optimize each person's health, could accurately diagnose the root cause of any disease, could generate new personalized therapies (even if they didn't exist yet) to treat any serious disease .

Imagine an AI that could invent a protocol to fuse atomic nuclei in a way that safely produces more energy than it consumes, unlocking nuclear fusion as a cheap, sustainable, infinitely abundant of human energy.

All these scenarios are still fantasies today and are out of reach for today’s artificial intelligence. The point is that the true potential of AI lies in the path that leads to the development of new forms of intelligence that are completely unlike anything humans can do. If AI can achieve such a goal, who cares if it is "universal" in the sense of matching human capabilities overall?

Positioning ourselves as “general artificial intelligence” limits and diminishes the technology’s potential. And—because human intelligence is not general intelligence, which does not exist—it is conceptually incoherent in the first place.

What is it like to be an artificial intelligence?

This brings us to a related topic in the big picture of artificial intelligence, which is currently receiving a lot of public attention: the question of whether artificial intelligence is, or ever will be, sentient.

Google engineer Blake Lemoine sparked a wave of controversy and commentary last month when he publicly asserted that one of Google's large language models had become aware. (Before forming any definite opinions, it's worth reading the full transcript of the discussion between Lemoine and AI for yourself.)

Most people — especially AI experts — think Lemoine's claims are wrong and inaccurate. reasonable.

Google said in its official response: "Our team has reviewed Black's concerns and informed him that the evidence does not support his claims." Stanford University professor Erik Brynjolfsson believes that sensory artificial intelligence may still be 50 years away time. Gary Marcus chimed in, calling Lemoine's claims "nonsense," concluding that "there's nothing to see here."

The problem with this entire discussion—including the experts’ dismissal of it—is that the existence or absence of perception is, by definition, unprovable, unfalsifiable, and unknowable.

When we talk about perception, we are referring to the agent’s subjective inner experience, not to any external intellectual manifestation. No one—not Blake Lemoine, not Erik Brynjolfsson, not Gary Marcus—can be entirely sure what highly complex artificial neural networks do or do not experience internally.

In 1974, the philosopher Thomas Nagel published an article titled "What is it like to be a bat?" "Article. One of the most influential philosophical papers of the 20th century, this article boiled down the notoriously elusive concept of consciousness into a simple, intuitive definition: An agent is conscious if there is something willing to be that agent . For example, being my next door neighbor or even his dog is something; but being his mailbox is nothing like it.

A key message of the paper is that it is impossible to know exactly what it is like to be another organism or species in a meaningful way. The more unlike us another organism or species is, the more inaccessible its internal experience will be.

Nagel used bats as an example to illustrate this point. He chose bats because, as mammals, they are highly complex creatures, but their experience of life is very different from ours: they fly, they use sonar as their primary means of perceiving the world, and so on.

As Nagel puts it (it is worth quoting several paragraphs from the paper in full):

"Our own experience provides the basic material for our imagination, and therefore the scope of imagination is limited .Imagine a person with webbed arms that allow him to fly around at dusk and dawn and bugs in his mouth, which doesn't help; a person with very poor eyesight who perceives the world around him through a system of reflected high-frequency sound signals ;The guy hangs upside down in the attic all day long.

"As far as I can imagine (which isn't very far off), it only tells me what it would be like to act like a bat. But that's not the problem. I wonder what it feels like for a bat to be a bat. However, if I tried to imagine this, I would be limited to the resources of my own mind, which are insufficient for the task. I cannot achieve it by imagining additions to my present experience, or by imagining fragments gradually subtracted from it, or by imagining some combination of additions, subtractions, and modifications. ”

Artificial neural networks are more alien and inaccessible to us humans than bats, which are at least mammals and carbon-based life forms.

Likewise, too many commenters are The fundamental mistake made on this topic (often without even thinking about it) is to assume that we can simply map our expectations of human perception or intelligence to artificial intelligence. way to determine or even think about the intrinsic experience of AI. We simply cannot be sure.

So how can we approach the topic of AI perception in a productive way?

We can start with Turing ( Alan Turing was inspired by the Turing Test, first proposed in 1950. Often criticized or misunderstood, and certainly imperfect, the Turing Test has stood the test of time as a reference point in the field of AI because it captures Certain fundamental insights into the nature of machine intelligence.

The Turing Test acknowledges and accepts the reality that we will never have direct access to the internal experience of an artificial intelligence. Its entire premise is that if we want to measure the intelligence of an artificial intelligence, Our only option is to observe its behavior and draw appropriate inferences. (To be clear, Turing was concerned with assessing a machine's ability to think, not necessarily its ability to feel; however, for our purposes In other words, what is relevant is the fundamentals.)

Douglas Hofstadter articulated this idea particularly eloquently: "How do you know that when I'm talking to you, anything similar to what you're talking about is going on inside me? 'Thinking' thing? The Turing test is an amazing probe—like a particle accelerator in physics. Just like in physics, when you want to understand what's going on at the atomic or subatomic level, since you can't see it directly, you scatter accelerated particles away from relevant targets and observe their behavior. From this you can infer the internal properties of the target. The Turing Test extends this idea to the mind. It treats ideas as "objects" that are not directly visible but whose structure can be inferred more abstractly. By 'distracting' the problem from the target's mind, you can understand its inner workings, just like in physics. ”

To make any progress in discussions about artificial intelligence perception, we must orient ourselves toward observable representations as proxies for internal experience; otherwise, we will end up in a loose, empty, dead-end world. Going in circles in the debate.

Erik Brynjolfsson is convinced that today’s AI is not sentient. However, his comments indicate that he believes AI will eventually be sentient. When he encounters a truly sentient AI , how would he know? What would he be looking for?

You Are What You Do

In debates about AI, skeptics often describe the technology in simplified terms that downplay its capabilities.

As one AI researcher put it in response to the Blake Lemoine news: "The hope of gaining awareness, understanding, or common sense from symbolic and data processing using higher-dimensional parametric functions is mysterious." In a recent blog post, Gary Marcus argued that today’s AI models aren’t even “telepathically intelligent” because “all they do is match patterns and pull data from massive statistical databases.” He argued that Google’s large The language model LaMDA is just a "spreadsheet of words".

This line of reasoning is misleading and trivial. After all, if we so choose, we can build human intelligence in a similarly simplified way: our brains are "just" a large collection of neurons interconnected in specific ways, "just" a collection of basic chemical reactions within our skulls.

But this misses the point. The power and magic of human intelligence lies not in specific mechanisms but in the incredible ability to emerge in some way. Simple basic functions can produce profoundly intellectual systems.

Ultimately, we must judge artificial intelligence based on its capabilities.

If we compare the state of artificial intelligence five years ago to the state of technology today, there is no doubt that its capabilities and depth have increased significantly (and are still accelerating) due to breakthroughs in areas such as self-supervised learning. Ways to scale, transformer and reinforcement learning.

Artificial intelligence is not like human intelligence. When and if an AI becomes sentient—when and if it ever becomes, in Nagel's formulation, "like something"—it will be incomparable to what it is like to be human. Artificial intelligence is its own unique, unfamiliar, fascinating, and rapidly evolving form of cognition.

What matters is what artificial intelligence can achieve. Breakthroughs in fundamental science like AlphaFold, addressing species-level challenges like climate change, promoting human health and longevity, and deepening our understanding of how the universe works—these results are a true test of the power and complexity of AI.

The above is the detailed content of General artificial intelligence, artificial intelligence perception, and large language models. For more information, please follow other related articles on the PHP Chinese website!

How to Run LLM Locally Using LM Studio? - Analytics VidhyaApr 19, 2025 am 11:38 AM

How to Run LLM Locally Using LM Studio? - Analytics VidhyaApr 19, 2025 am 11:38 AMRunning large language models at home with ease: LM Studio User Guide In recent years, advances in software and hardware have made it possible to run large language models (LLMs) on personal computers. LM Studio is an excellent tool to make this process easy and convenient. This article will dive into how to run LLM locally using LM Studio, covering key steps, potential challenges, and the benefits of having LLM locally. Whether you are a tech enthusiast or are curious about the latest AI technologies, this guide will provide valuable insights and practical tips. Let's get started! Overview Understand the basic requirements for running LLM locally. Set up LM Studi on your computer

Guy Peri Helps Flavor McCormick's Future Through Data TransformationApr 19, 2025 am 11:35 AM

Guy Peri Helps Flavor McCormick's Future Through Data TransformationApr 19, 2025 am 11:35 AMGuy Peri is McCormick’s Chief Information and Digital Officer. Though only seven months into his role, Peri is rapidly advancing a comprehensive transformation of the company’s digital capabilities. His career-long focus on data and analytics informs

What is the Chain of Emotion in Prompt Engineering? - Analytics VidhyaApr 19, 2025 am 11:33 AM

What is the Chain of Emotion in Prompt Engineering? - Analytics VidhyaApr 19, 2025 am 11:33 AMIntroduction Artificial intelligence (AI) is evolving to understand not just words, but also emotions, responding with a human touch. This sophisticated interaction is crucial in the rapidly advancing field of AI and natural language processing. Th

12 Best AI Tools for Data Science Workflow - Analytics VidhyaApr 19, 2025 am 11:31 AM

12 Best AI Tools for Data Science Workflow - Analytics VidhyaApr 19, 2025 am 11:31 AMIntroduction In today's data-centric world, leveraging advanced AI technologies is crucial for businesses seeking a competitive edge and enhanced efficiency. A range of powerful tools empowers data scientists, analysts, and developers to build, depl

AV Byte: OpenAI's GPT-4o Mini and Other AI InnovationsApr 19, 2025 am 11:30 AM

AV Byte: OpenAI's GPT-4o Mini and Other AI InnovationsApr 19, 2025 am 11:30 AMThis week's AI landscape exploded with groundbreaking releases from industry giants like OpenAI, Mistral AI, NVIDIA, DeepSeek, and Hugging Face. These new models promise increased power, affordability, and accessibility, fueled by advancements in tr

Perplexity's Android App Is Infested With Security Flaws, Report FindsApr 19, 2025 am 11:24 AM

Perplexity's Android App Is Infested With Security Flaws, Report FindsApr 19, 2025 am 11:24 AMBut the company’s Android app, which offers not only search capabilities but also acts as an AI assistant, is riddled with a host of security issues that could expose its users to data theft, account takeovers and impersonation attacks from malicious

Everyone's Getting Better At Using AI: Thoughts On Vibe CodingApr 19, 2025 am 11:17 AM

Everyone's Getting Better At Using AI: Thoughts On Vibe CodingApr 19, 2025 am 11:17 AMYou can look at what’s happening in conferences and at trade shows. You can ask engineers what they’re doing, or consult with a CEO. Everywhere you look, things are changing at breakneck speed. Engineers, and Non-Engineers What’s the difference be

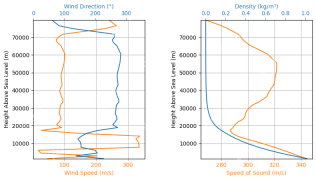

Rocket Launch Simulation and Analysis using RocketPy - Analytics VidhyaApr 19, 2025 am 11:12 AM

Rocket Launch Simulation and Analysis using RocketPy - Analytics VidhyaApr 19, 2025 am 11:12 AMSimulate Rocket Launches with RocketPy: A Comprehensive Guide This article guides you through simulating high-power rocket launches using RocketPy, a powerful Python library. We'll cover everything from defining rocket components to analyzing simula

Hot AI Tools

Undresser.AI Undress

AI-powered app for creating realistic nude photos

AI Clothes Remover

Online AI tool for removing clothes from photos.

Undress AI Tool

Undress images for free

Clothoff.io

AI clothes remover

Video Face Swap

Swap faces in any video effortlessly with our completely free AI face swap tool!

Hot Article

Hot Tools

Atom editor mac version download

The most popular open source editor

ZendStudio 13.5.1 Mac

Powerful PHP integrated development environment

PhpStorm Mac version

The latest (2018.2.1) professional PHP integrated development tool

Safe Exam Browser

Safe Exam Browser is a secure browser environment for taking online exams securely. This software turns any computer into a secure workstation. It controls access to any utility and prevents students from using unauthorized resources.

SAP NetWeaver Server Adapter for Eclipse

Integrate Eclipse with SAP NetWeaver application server.