Home >Web Front-end >JS Tutorial >Learn javascript execution context with me_javascript skills

Learn javascript execution context with me_javascript skills

- WBOYWBOYWBOYWBOYWBOYWBOYWBOYWBOYWBOYWBOYWBOYWBOYWBOriginal

- 2016-05-16 15:31:311190browse

In this article, I will delve into the most basic part of JavaScript - execution context. After reading this article, you should have a clear idea of what the interpreter does, why functions and variables can be used before they are declared, and how their values are determined.

1. EC—execution environment or execution context

Whenever the controller reaches the ECMAScript executable code, the controller enters an execution context (what a fancy concept).

In JavaScript, EC is divided into three types:

- Global level code –– This is the default code running environment. Once the code is loaded, this is the environment that the engine first enters.

- Function level code – When a function is executed, the code in the function body is run.

- Eval’s code –– Code that runs within the Eval function.

EC establishment is divided into two phases: Entering the execution context (creation phase) and execution phase (activation/execution of code).

1) Entering the context phase: occurs when a function is called, but before executing specific code (for example, before specifying function parameters)

Create a scope chain (Scope Chain)

Create variables, functions and parameters.

Find the value of "this".

2), code execution stage:

Variable assignment

Function reference

Interpret/execute other code.

We can think of EC as an object.

EC={

VO:{/* 函数中的arguments对象, 参数, 内部的变量以及函数声明 */},

this:{},

Scope:{ /* VO以及所有父执行上下文中的VO */}

}

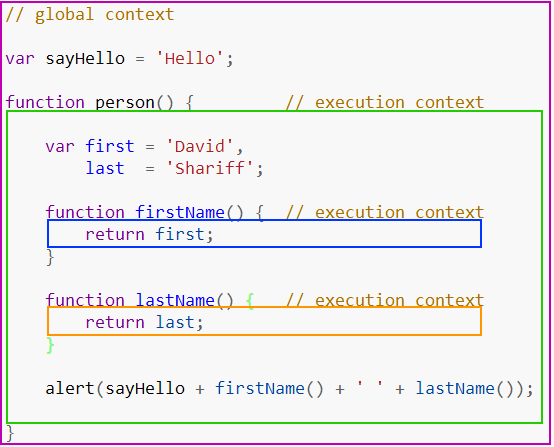

Now let’s look at a code example with global and function context:

A very simple example, we have a global context surrounded by a purple border and three different function contexts surrounded by green, blue and orange borders. Only the global context can be accessed by any other context.

You can have as many function contexts as you like. Each time you call a function to create a new context, a private scope will be created. Any variables declared inside the function cannot be directly accessed outside the current function scope. In the above example, the function can access variable declarations outside the current context, but cannot access internal variable/function declarations in the external context. Why does this happen? How exactly is the code interpreted?

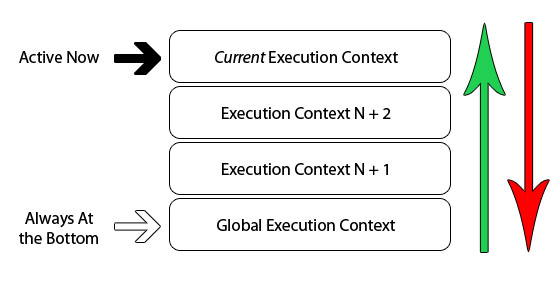

2. ECS—execution context stack

A series of execution contexts of activities logically form a stack. The bottom of the stack is always the global context, and the top of the stack is the current (active) execution context. When switching between different execution contexts (exiting and entering a new execution context), the stack will be modified (by pushing or popping the stack).

Push: Global EC—>Local EC1—>Local EC2—>Current EC

Pop: Global EC<—Local EC1<—Local EC2<—Current EC

We can use an array to represent the environment stack:

ECS=[局部EC,全局EC];

Every time the controller enters a function (even if the function is called recursively or serves as a constructor), a push operation will occur. The process is similar to the push and pop operations of JavaScript arrays.

The JavaScript interpreter in the browser is implemented as a single thread. This means that only one thing can happen at a time, and other lines or events will be queued in what is called the execution stack. The diagram below is an abstract view of a single-thread stack:

We already know that when the browser first loads your script, it will enter the global execution context by default. If, you call a function in your global code, your program's timing will enter the called function and thread a new execution context, pushing the newly created context onto the top of the execution stack.

The same thing will happen here if you call other functions inside the current function. The execution flow of the code enters the inner function, which creates a new execution context and pushes it to the top of the execution stack. The browser will always execute the execution context on the top of the stack. Once the current context function finishes executing, it will be popped from the top of the stack and transfer context control to the current stack. The following example shows the execution stack call process of a recursive function:

(function foo(i) {

if (i === 3) {

return;

}

else {

foo(++i);

}

}(0));

这代码调用自己三次,每次给i的值加一。每次foo函数被调用,将创建一个新的执行上下文。一旦上下文执行完毕,它将被从栈顶弹出,并将控制权返回给下面的上下文,直到只剩全局上下文能为止。

有5个需要记住的关键点,关于执行栈(调用栈):

- 单线程。

- 同步执行。

- 一个全局上下文。

- 无限制函数上下文。

- 每次函数被调用创建新的执行上下文,包括调用自己。

3、VO—变量对象

每一个EC都对应一个变量对象VO,在该EC中定义的所有变量和函数都存放在其对应的VO中。

VO分为全局上下文VO(全局对象,Global object,我们通常说的global对象)和函数上下文的AO。

VO: {

// 上下文中的数据 ( 函数形参(function arguments), 函数声明(FD),变量声明(var))

}

1)、进入执行上下文时,VO的初始化过程具体如下:

函数的形参(当进入函数执行上下文时)—— 变量对象的一个属性,其属性名就是形参的名字,其值就是实参的值;对于没有传递的参数,其值为undefined;

函数声明(FunctionDeclaration, FD) —— 变量对象的一个属性,其属性名和值都是函数对象创建出来的;如果变量对象已经包含了相同名字的属性,则替换它的值;

变量声明(var,VariableDeclaration) —— 变量对象的一个属性,其属性名即为变量名,其值为undefined;如果变量名和已经声明的函数名或者函数的参数名相同,则不会影响已经存在的属性。

注意:该过程是有先后顺序的。

2)、 执行代码阶段时,VO中的一些属性undefined值将会确定。

4、AO活动对象

在函数的执行上下文中,VO是不能直接访问的。它主要扮演被称作活跃对象(activation object)(简称:AO)的角色。

这句话怎么理解呢,就是当EC环境为函数时,我们访问的是AO,而不是VO。

VO(functionContext) === AO;

AO是在进入函数的执行上下文时创建的,并为该对象初始化一个arguments属性,该属性的值为Arguments对象。

AO = {

arguments: {

callee:,

length:,

properties-indexes: //函数传参参数值

}

};

FD的形式只能是如下这样:

function f(){

}

当函数被调用是executionContextObj被创建,但在实际函数执行之前。这是我们上面提到的第一阶段,创建阶段。在此阶段,解释器扫描传递给函数的参数或arguments,本地函数声明和本地变量声明,并创建executionContextObj对象。扫描的结果将完成变量对象的创建。

内部的执行顺序如下:

1、查找调用函数的代码。

2、执行函数代码之前,先创建执行上下文。

3、进入创建阶段:

- 初始化作用域链:

- 创建变量对象:

- 创建arguments对象,检查上下文,初始化参数名称和值并创建引用的复制。

- 扫描上下文的函数声明:为发现的每一个函数,在变量对象上创建一个属性(确切的说是函数的名字),其有一个指向函数在内存中的引用。如果函数的名字已经存在,引用指针将被重写。

- 扫面上下文的变量声明:为发现的每个变量声明,在变量对象上创建一个属性——就是变量的名字,并且将变量的值初始化为undefined,如果变量的名字已经在变量对象里存在,将不会进行任何操作并继续扫描。

- 求出上下文内部“this”的值。

4、激活/代码执行阶段:

在当前上下文上运行/解释函数代码,并随着代码一行行执行指派变量的值。

示例

1、具体实例

function foo(i) {

var a = ‘hello‘;

var b = function privateB() {

};

function c() {

}

}

foo(22);

当调用foo(22)时,创建状态像下面这样:

fooExecutionContext = {

scopeChain: { ... },

variableObject: {

arguments: {

0: 22,

length: 1

},

i: 22,

c: pointer to function c()

a: undefined,

b: undefined

},

this: { ... }

}

真如你看到的,创建状态负责处理定义属性的名字,不为他们指派具体的值,以及形参/实参的处理。一旦创建阶段完成,执行流进入函数并且激活/代码执行阶段,看下函数执行完成后的样子:

fooExecutionContext = {

scopeChain: { ... },

variableObject: {

arguments: {

0: 22,

length: 1

},

i: 22,

c: pointer to function c()

a: ‘hello‘,

b: pointer to function privateB()

},

this: { ... }

}

2、VO示例:

alert(x); // function

var x = 10;

alert(x); // 10

x = 20;

function x() {};

alert(x); // 20

进入执行上下文时,

ECObject={

VO:{

x:<reference to FunctionDeclaration "x">

}

};

执行代码时:

ECObject={

VO:{

x:20 //与函数x同名,替换掉,先是10,后变成20

}

};

对于以上的过程,我们详细解释下。

在进入上下文的时候,VO会被填充函数声明; 同一阶段,还有变量声明“x”,但是,正如此前提到的,变量声明是在函数声明和函数形参之后,并且,变量声明不会对已经存在的同样名字的函数声明和函数形参发生冲突。因此,在进入上下文的阶段,VO填充为如下形式:

VO = {};

VO['x'] = <引用了函数声明'x'>

// 发现var x = 10;

// 如果函数“x”还未定义

// 则 "x" 为undefined, 但是,在我们的例子中

// 变量声明并不会影响同名的函数值

VO['x'] = <值不受影响,仍是函数>

执行代码阶段,VO被修改如下:

VO['x'] = 10; VO['x'] = 20;

如下例子再次看到在进入上下文阶段,变量存储在VO中(因此,尽管else的代码块永远都不会执行到,而“b”却仍然在VO中)

if (true) {

var a = 1;

} else {

var b = 2;

}

alert(a); // 1

alert(b); // undefined, but not "b is not defined"

3、AO示例:

function test(a, b) {

var c = 10;

function d() {}

var e = function _e() {};

(function x() {});

}

test(10); // call

当进入test(10)的执行上下文时,它的AO为:

testEC={

AO:{

arguments:{

callee:test

length:1,

0:10

},

a:10,

c:undefined,

d:<reference to FunctionDeclaration "d">,

e:undefined

}

};

由此可见,在建立阶段,VO除了arguments,函数的声明,以及参数被赋予了具体的属性值,其它的变量属性默认的都是undefined。函数表达式不会对VO造成影响,因此,(function x() {})并不会存在于VO中。

当执行 test(10)时,它的AO为:

testEC={

AO:{

arguments:{

callee:test,

length:1,

0:10

},

a:10,

c:10,

d:<reference to FunctionDeclaration "d">,

e:<reference to FunctionDeclaration "e">

}

};

可见,只有在这个阶段,变量属性才会被赋具体的值。

5、提升(Hoisting)解密

在之前的JavaScript Item中降到了变量和函数声明被提升到函数作用域的顶部。然而,没有人解释为什么会发生这种情况的细节,学习了上面关于解释器如何创建active活动对象的新知识,很容易明白为什么。看下面的例子:

(function() {

console.log(typeof foo); // 函数指针

console.log(typeof bar); // undefined

var foo = ‘hello‘,

bar = function() {

return ‘world‘;

};

function foo() {

return ‘hello‘;

}

}());

我们能回答下面的问题:

1、为什么我们能在foo声明之前访问它?

如果我们跟随创建阶段,我们知道变量在激活/代码执行阶段已经被创建。所以在函数开始执行之前,foo已经在活动对象里面被定义了。

2、foo被声明了两次,为什么foo显示为函数而不是undefined或字符串?

尽管foo被声明了两次,我们知道从创建阶段函数已经在活动对象里面被创建,这一过程发生在变量创建之前,并且如果属性名已经在活动对象上存在,我们仅仅更新引用。

因此,对foo()函数的引用首先被创建在活动对象里,并且当我们解释到var foo时,我们看见foo属性名已经存在,所以代码什么都不做并继续执行。

3、为什么bar的值是undefined?

bar实际上是一个变量,但变量的值是函数,并且我们知道变量在创建阶段被创建但他们被初始化为undefined。

以上就是本文的全部内容,有详细的问题解答,示例代码,帮助大家更加了解javascript的执行上下文,希望大家喜欢这篇文章。

Related articles

See more- An in-depth analysis of the Bootstrap list group component

- Detailed explanation of JavaScript function currying

- Complete example of JS password generation and strength detection (with demo source code download)

- Angularjs integrates WeChat UI (weui)

- How to quickly switch between Traditional Chinese and Simplified Chinese with JavaScript and the trick for websites to support switching between Simplified and Traditional Chinese_javascript skills