Python装饰器的理解及应用方式

- WBOYWBOYWBOYWBOYWBOYWBOYWBOYWBOYWBOYWBOYWBOYWBOYWB转载

- 2023-05-08 08:10:101643浏览

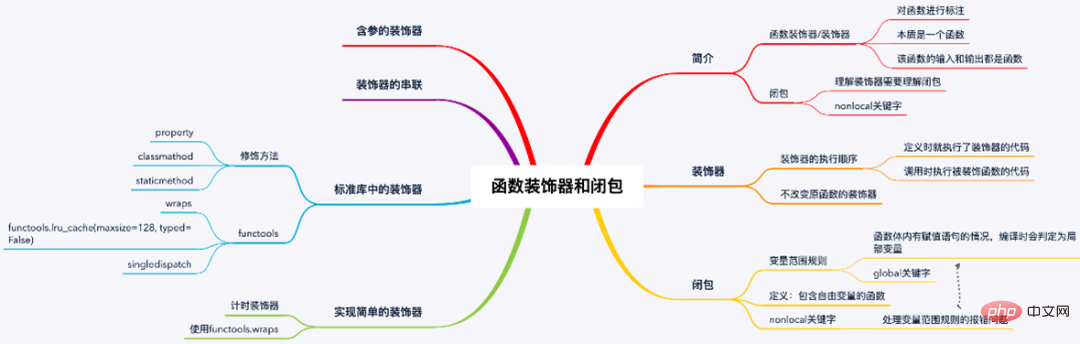

装饰器(decorator)是一种高级Python语法。可以对一个函数、方法或者类进行加工。在Python中,我们有多种方法对函数和类进行加工,相对于其它方式,装饰器语法简单,代码可读性高。因此,装饰器在Python项目中有广泛的应用。修饰器经常被用于有切面需求的场景,较为经典的有插入日志、性能测试、事务处理, Web权限校验, Cache等。

装饰器的优点是能够抽离出大量函数中与函数功能本身无关的雷同代码并继续重用。即,可以将函数“修饰”为完全不同的行为,可以有效的将业务逻辑正交分解。概括的讲,装饰器的作用就是为已经存在的对象添加额外的功能。例如记录日志,需要对某些函数进行记录。笨的办法,每个函数加入代码,如果代码变了,就悲催了。装饰器的办法,定义一个专门日志记录的装饰器,对需要的函数进行装饰。

Python 的 Decorator在使用上和Java/C#的Annotation很相似,都是在方法名前面加一个@XXX注解来为这个方法装饰一些东西。但是,Java/C#的Annotation也很让人望而却步,在使用它之前你需要了解一堆Annotation的类库文档,让人感觉就是在学另外一门语言。而Python使用了一种相对于Decorator Pattern和Annotation来说非常优雅的方法,这种方法不需要你去掌握什么复杂的OO模型或是Annotation的各种类库规定,完全就是语言层面的玩法:一种函数式编程的技巧。

装饰器背后的原理

在Python中,装饰器实现是十分方便。原因是:函数可以被扔来扔去。

Python的函数就是对象

要理解装饰器,就必须先知道,在Python里,函数也是对象(functions are objects)。明白这一点非常重要,让我们通过一个例子来看看为什么。

def shout(word="yes"): **return** word.capitalize() + "!" print(shout()) # outputs : 'Yes!' # 作为一个对象,你可以像其他对象一样把函数赋值给其他变量 scream = shout # 注意我们没有用括号:我们不是在调用函数, # 而是把函数'shout'的值绑定到'scream'这个变量上 # 这也意味着你可以通过'scream'这个变量来调用'shout'函数 print(scream()) # outputs : 'Yes!' # 不仅如此,这也还意味着你可以把原来的名字'shout'删掉, # 而这个函数仍然可以通过'scream'来访问 del shout **try**: print(shout()) **except** NameError as e: print(e) # outputs: "name 'shout' is not defined" print(scream()) # outputs: 'Yes!'

Python 函数的另一个有趣的特性是,它们可以在另一个函数体内定义。

def talk(): # 你可以在 'talk' 里动态的(on the fly)定义一个函数... **def** whisper(word="yes"): **return** word.lower() + "..." # ... 然后马上调用它! print(whisper()) # 每当调用'talk',都会定义一次'whisper',然后'whisper'在'talk'里被调用 talk() # outputs: # "yes..." # 但是"whisper" 在 "talk"外并不存在: **try**: print(whisper()) **except** NameError as e: print(e) # outputs : "name 'whisper' is not defined"

函数引用(Functions references)

你刚刚已经知道了,Python的函数也是对象,因此:

- 可以被赋值给变量

- 可以在另一个函数体内定义

那么,这样就意味着一个函数可以返回另一个函数:

def get_talk(type="shout"):

# 我们先动态定义一些函数

**def** shout(word="yes"):

**return** word.capitalize() + "!"

**def** whisper(word="yes"):

**return** word.lower() + "..."

# 然后返回其中一个

**if** type == "shout":

# 注意:我们是在返回函数对象,而不是调用函数,所以不要用到括号 "()"

**return** shout

**else**:

**return** whisper

# 那你改如何使用d呢?

# 先把函数赋值给一个变量

talk = get_talk()

# 你可以发现 "talk" 其实是一个函数对象:

print(talk)

# outputs : <function shout at 0xb7ea817c>

# 这个对象就是 get_talk 函数返回的:

print(talk())

# outputs : Yes!

# 你甚至还可以直接这样使用:

print(get_talk("whisper")())

# outputs : yes...既然可以返回一个函数,那么也就可以像参数一样传递:

def shout(word="yes"):

**return** word.capitalize() + "!"

scream = shout

**def** do_something_before(func):

print("I do something before then I call the function you gave me")

print(func())

do_something_before(scream)

# outputs:

# I do something before then I call the function you gave me

# Yes!装饰器实战

现在已经具备了理解装饰器的所有基础知识了。装饰器也就是一种包装材料,它们可以让你在执行被装饰的函数之前或之后执行其他代码,而且不需要修改函数本身。

手工制作的装饰器

# 一个装饰器是一个需要另一个函数作为参数的函数

**def** my_shiny_new_decorator(a_function_to_decorate):

# 在装饰器内部动态定义一个函数:wrapper(原意:包装纸).

# 这个函数将被包装在原始函数的四周

# 因此就可以在原始函数之前和之后执行一些代码.

**def** the_wrapper_around_the_original_function():

# 把想要在调用原始函数前运行的代码放这里

print("Before the function runs")

# 调用原始函数(需要带括号)

a_function_to_decorate()

# 把想要在调用原始函数后运行的代码放这里

print("After the function runs")

# 直到现在,"a_function_to_decorate"还没有执行过 (HAS NEVER BEEN EXECUTED).

# 我们把刚刚创建的 wrapper 函数返回.

# wrapper 函数包含了这个函数,还有一些需要提前后之后执行的代码,

# 可以直接使用了(It's ready to use!)

**return** the_wrapper_around_the_original_function

# Now imagine you create a function you don't want to ever touch again.

**def** a_stand_alone_function():

print("I am a stand alone function, don't you dare modify me")

a_stand_alone_function()

# outputs: I am a stand alone function, don't you dare modify me

# 现在,你可以装饰一下来修改它的行为.

# 只要简单的把它传递给装饰器,后者能用任何你想要的代码动态的包装

# 而且返回一个可以直接使用的新函数:

a_stand_alone_function_decorated = my_shiny_new_decorator(a_stand_alone_function)

a_stand_alone_function_decorated()

# outputs:

# Before the function runs

# I am a stand alone function, don't you dare modify me

# After the function runs装饰器的语法糖

我们用装饰器的语法来重写一下前面的例子:

# 一个装饰器是一个需要另一个函数作为参数的函数

**def** my_shiny_new_decorator(a_function_to_decorate):

# 在装饰器内部动态定义一个函数:wrapper(原意:包装纸).

# 这个函数将被包装在原始函数的四周

# 因此就可以在原始函数之前和之后执行一些代码.

**def** the_wrapper_around_the_original_function():

# 把想要在调用原始函数前运行的代码放这里

print("Before the function runs")

# 调用原始函数(需要带括号)

a_function_to_decorate()

# 把想要在调用原始函数后运行的代码放这里

print("After the function runs")

# 直到现在,"a_function_to_decorate"还没有执行过 (HAS NEVER BEEN EXECUTED).

# 我们把刚刚创建的 wrapper 函数返回.

# wrapper 函数包含了这个函数,还有一些需要提前后之后执行的代码,

# 可以直接使用了(It's ready to use!)

**return** the_wrapper_around_the_original_function

@my_shiny_new_decorator

**def** another_stand_alone_function():

print("Leave me alone")

another_stand_alone_function()

# outputs:

# Before the function runs

# Leave me alone

# After the function runs是的,这就完了,就这么简单。@decorator 只是下面这条语句的简写(shortcut):

another_stand_alone_function = my_shiny_new_decorator(another_stand_alone_function)

装饰器语法糖其实就是装饰器模式的一个Python化的变体。为了方便开发,Python已经内置了好几种经典的设计模式,比如迭代器(iterators)。当然,你还可以堆积使用装饰器:

def bread(func):

**def** wrapper():

print("</''''''>")

func()

print("<______/>")

**return** wrapper

**def** ingredients(func):

**def** wrapper():

print("#tomatoes#")

func()

print("~salad~")

**return** wrapper

**def** sandwich(food="--ham--"):

print(food)

sandwich()

# outputs: --ham--

sandwich = bread(ingredients(sandwich))

sandwich()

# outputs:

# </''''''>

# #tomatoes#

# --ham--

# ~salad~

# <______/>用Python的装饰器语法表示:

def bread(func):

**def** wrapper():

print("</''''''>")

func()

print("<______/>")

**return** wrapper

**def** ingredients(func):

**def** wrapper():

print("#tomatoes#")

func()

print("~salad~")

**return** wrapper

@bread

@ingredients

**def** sandwich(food="--ham--"):

print(food)

sandwich()

# outputs:

# </''''''>

# #tomatoes#

# --ham--

# ~salad~

# <______/>装饰器放置的顺序也很重要:

def bread(func):

**def** wrapper():

print("</''''''>")

func()

print("<______/>")

**return** wrapper

**def** ingredients(func):

**def** wrapper():

print("#tomatoes#")

func()

print("~salad~")

**return** wrapper

@ingredients

@bread

**def** strange_sandwich(food="--ham--"):

print(food)

strange_sandwich()

# outputs:

##tomatoes#

# </''''''>

# --ham--

# <______/>

# ~salad~给装饰器函数传参

# 这不是什么黑色魔法(black magic),你只是必须让wrapper传递参数:

**def** a_decorator_passing_arguments(function_to_decorate):

**def** a_wrapper_accepting_arguments(arg1, arg2):

print("I got args! Look:", arg1, arg2)

function_to_decorate(arg1, arg2)

**return** a_wrapper_accepting_arguments

# 当你调用装饰器返回的函数式,你就在调用wrapper,而给wrapper的

# 参数传递将会让它把参数传递给要装饰的函数

@a_decorator_passing_arguments

**def** print_full_name(first_name, last_name):

print("My name is", first_name, last_name)

print_full_name("Peter", "Venkman")

# outputs:

# I got args! Look: Peter Venkman

# My name is Peter Venkman含参数的装饰器

在上面的装饰器调用中,比如@decorator,该装饰器默认它后面的函数是唯一的参数。装饰器的语法允许我们调用decorator时,提供其它参数,比如@decorator(a)。这样,就为装饰器的编写和使用提供了更大的灵活性。

# a new wrapper layer

**def** pre_str(pre=''):

# old decorator

**def** decorator(F):

**def** new_F(a, b):

print(pre + " input", a, b)

**return** F(a, b)

**return** new_F

**return** decorator

# get square sum

@pre_str('^_^')

**def** square_sum(a, b):

**return** a ** 2 + b ** 2

# get square diff

@pre_str('T_T')

**def** square_diff(a, b):

**return** a ** 2 - b ** 2

print(square_sum(3, 4))

print(square_diff(3, 4))

# outputs:

# ('^_^ input', 3, 4)

# 25

# ('T_T input', 3, 4)

# -7上面的pre_str是允许参数的装饰器。它实际上是对原有装饰器的一个函数封装,并返回一个装饰器。我们可以将它理解为一个含有环境参量的闭包。当我们使用@pre_str(‘^_^’)调用的时候,Python能够发现这一层的封装,并把参数传递到装饰器的环境中。该调用相当于:

square_sum = pre_str('^_^') (square_sum)装饰“类中的方法”

Python的一个伟大之处在于:方法和函数几乎是一样的(methods and functions are really the same),除了方法的第一个参数应该是当前对象的引用(也就是 self)。这也就意味着只要记住把 self 考虑在内,你就可以用同样的方法给方法创建装饰器:

def method_friendly_decorator(method_to_decorate):

**def** wrapper(self, lie):

lie = lie - 3# very friendly, decrease age even more :-)

**return** method_to_decorate(self, lie)

**return** wrapper

**class** Lucy(object):

**def** __init__(self):

self.age = 32

@method_friendly_decorator

**def** say_your_age(self, lie):

print("I am %s, what did you think?" % (self.age + lie))

l = Lucy()

l.say_your_age(-3)

# outputs: I am 26, what did you think?当然,如果你想编写一个非常通用的装饰器,可以用来装饰任意函数和方法,你就可以无视具体参数了,直接使用 *args, **kwargs 就行:

def a_decorator_passing_arbitrary_arguments(function_to_decorate):

# The wrapper accepts any arguments

**def** a_wrapper_accepting_arbitrary_arguments(*args, **kwargs):

print("Do I have args?:")

print(args)

print(kwargs)

# Then you unpack the arguments, here *args, **kwargs

# If you are not familiar with unpacking, check:

# http://www.saltycrane.com/blog/2008/01/how-to-use-args-and-kwargs-in-python/

function_to_decorate(*args, **kwargs)

**return** a_wrapper_accepting_arbitrary_arguments

@a_decorator_passing_arbitrary_arguments

**def** function_with_no_argument():

print("Python is cool, no argument here.")

function_with_no_argument()

# outputs

# Do I have args?:

# ()

# {}

# Python is cool, no argument here.

@a_decorator_passing_arbitrary_arguments

**def** function_with_arguments(a, b, c):

print(a, b, c)

function_with_arguments(1, 2, 3)

# outputs

# Do I have args?:

# (1, 2, 3)

# {}

# 1 2 3

@a_decorator_passing_arbitrary_arguments

**def** function_with_named_arguments(a, b, c, platypus="Why not ?"):

print("Do %s, %s and %s like platypus? %s" % (a, b, c, platypus))

function_with_named_arguments("Bill", "Linus", "Steve", platypus="Indeed!")

# outputs

# Do I have args ? :

# ('Bill', 'Linus', 'Steve')

# {'platypus': 'Indeed!'}

# Do Bill, Linus and Steve like platypus? Indeed!

**class** Mary(object):

**def** __init__(self):

self.age = 31

@a_decorator_passing_arbitrary_arguments

**def** say_your_age(self, lie=-3):# You can now add a default value

print("I am %s, what did you think ?" % (self.age + lie))

m = Mary()

m.say_your_age()

# outputs

# Do I have args?:

# (<__main__.Mary object at 0xb7d303ac>,)

# {}

# I am 28, what did you think?装饰类

在上面的例子中,装饰器接收一个函数,并返回一个函数,从而起到加工函数的效果。在Python 2.6以后,装饰器被拓展到类。一个装饰器可以接收一个类,并返回一个类,从而起到加工类的效果。

def decorator(aClass):

**class** newClass:

**def** __init__(self, age):

self.total_display = 0

self.wrapped = aClass(age)

**def** display(self):

self.total_display += 1

print("total display", self.total_display)

self.wrapped.display()

**return** newClass

@decorator

**class** Bird:

**def** __init__(self, age):

self.age = age

**def** display(self):

print("My age is", self.age)

eagleLord = Bird(5)

**for** i **in** range(3):

eagleLord.display()在decorator中,我们返回了一个新类newClass。在新类中,我们记录了原来类生成的对象(self.wrapped),并附加了新的属性total_display,用于记录调用display的次数。我们也同时更改了display方法。通过修改,我们的Bird类可以显示调用display的次数了。

内置装饰器

Python中有三种我们经常会用到的装饰器, property、 staticmethod、 classmethod,他们有个共同点,都是作用于类方法之上。

property 装饰器

property 装饰器用于类中的函数,使得我们可以像访问属性一样来获取一个函数的返回值。

class XiaoMing: first_name = '明' last_name = '小' @property **def** full_name(self): **return** self.last_name + self.first_name xiaoming = XiaoMing() print(xiaoming.full_name)

例子中我们像获取属性一样获取 full_name 方法的返回值,这就是用 property 装饰器的意义,既能像属性一样获取值,又可以在获取值的时候做一些操作。

staticmethod 装饰器

staticmethod 装饰器同样是用于类中的方法,这表示这个方法将会是一个静态方法,意味着该方法可以直接被调用无需实例化,但同样意味着它没有 self 参数,也无法访问实例化后的对象。

class XiaoMing:

@staticmethod

**def** say_hello():

print('同学你好')

XiaoMing.say_hello()

# 实例化调用也是同样的效果

# 有点多此一举

xiaoming = XiaoMing()

xiaoming.say_hello()classmethod 装饰器

classmethod 依旧是用于类中的方法,这表示这个方法将会是一个类方法,意味着该方法可以直接被调用无需实例化,但同样意味着它没有 self 参数,也无法访问实例化后的对象。相对于 staticmethod 的区别在于它会接收一个指向类本身的 cls 参数。

class XiaoMing:

name = '小明'

@classmethod

**def** say_hello(cls):

print('同学你好, 我是' + cls.name)

print(cls)

XiaoMing.say_hello()wraps 装饰器

一个函数不止有他的执行语句,还有着 name(函数名),doc (说明文档)等属性,我们之前的例子会导致这些属性改变。

def decorator(func):

**def** wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

"""doc of wrapper"""

print('123')

**return** func(*args, **kwargs)

**return** wrapper

@decorator

**def** say_hello():

"""doc of say hello"""

print('同学你好')

print(say_hello.__name__)

print(say_hello.__doc__)由于装饰器返回了 wrapper 函数替换掉了之前的 say_hello 函数,导致函数名,帮助文档变成了 wrapper 函数的了。解决这一问题的办法是通过 functools 模块下的 wraps 装饰器。

from functools import wraps

**def** decorator(func):

@wraps(func)

**def** wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

"""doc of wrapper"""

print('123')

**return** func(*args, **kwargs)

**return** wrapper

@decorator

**def** say_hello():

"""doc of say hello"""

print('同学你好')

print(say_hello.__name__)

print(say_hello.__doc__)装饰器总结

装饰器的核心作用是name binding。这种语法是Python多编程范式的又一个体现。大部分Python用户都不怎么需要定义装饰器,但有可能会使用装饰器。鉴于装饰器在Python项目中的广泛使用,了解这一语法是非常有益的。

常见错误:“装饰器”=“装饰器模式”

设计模式是一个在计算机世界里鼎鼎大名的词。假如你是一名 Java 程序员,而你一点设计模式都不懂,那么我打赌你找工作的面试过程一定会度过的相当艰难。

但写 Python 时,我们极少谈起“设计模式”。虽然 Python 也是一门支持面向对象的编程语言,但它的鸭子类型设计以及出色的动态特性决定了,大部分设计模式对我们来说并不是必需品。所以,很多 Python 程序员在工作很长一段时间后,可能并没有真正应用过几种设计模式。

不过装饰器模式(Decorator Pattern)是个例外。因为 Python 的“装饰器”和“装饰器模式”有着一模一样的名字,我不止一次听到有人把它们俩当成一回事,认为使用“装饰器”就是在实践“装饰器模式”。但事实上,它们是两个完全不同的东西。

“装饰器模式”是一个完全基于“面向对象”衍生出的编程手法。它拥有几个关键组成:一个统一的接口定义、若干个遵循该接口的类、类与类之间一层一层的包装。最终由它们共同形成一种“装饰”的效果。

而 Python 里的“装饰器”和“面向对象”没有任何直接联系,**它完全可以只是发生在函数和函数间的把戏。事实上,“装饰器”并没有提供某种无法替代的功能,它仅仅就是一颗“语法糖”而已。下面这段使用了装饰器的代码:

@log_time @cache_result **def** foo(): pass

基本完全等同于:

def foo(): pass foo = log_time(cache_result(foo))

装饰器最大的功劳,在于让我们在某些特定场景时,可以写出更符合直觉、易于阅读的代码。它只是一颗“糖”,并不是某个面向对象领域的复杂编程模式。

以上是Python装饰器的理解及应用方式的详细内容。更多信息请关注PHP中文网其他相关文章!