When building software systems, it's crucial to manage codebase complexity.

Clean Code's Chapter 11 discusses designing modular systems that are easier to maintain and adapt over time.

We can use JavaScript examples to illustrate these concepts.

? The Problem with Large Systems

As systems grow, they naturally become more complex. This complexity can make it difficult to:

- Understand the system as a whole.

- Make changes without causing unintended side effects.

- Scale the system with new features or requirements.

A well-designed system should be easy to modify, testable, and scalable. The secret to achieving this lies in modularity and careful separation of concerns.

? Modularity: Divide and Conquer

At the heart of clean systems design is the principle of modularity. You make the system more manageable by breaking a large system into smaller, independent modules, each with a clear responsibility.

Each module should encapsulate a specific functionality, making the overall system easier to understand and change.

Example: Organizing a Shopping Cart System

Let’s imagine a shopping cart system in JavaScript. Instead of lumping all logic into a single file, you can break the system into several modules:

// cart.js

export class Cart {

constructor() {

this.items = [];

}

addItem(item) {

this.items.push(item);

}

getTotal() {

return this.items.reduce((total, item) => total + item.price, 0);

}

}

// item.js

export class Item {

constructor(name, price) {

this.name = name;

this.price = price;

}

}

// order.js

import { Cart } from './cart.js';

import { Item } from './item.js';

const cart = new Cart();

cart.addItem(new Item('Laptop', 1000));

cart.addItem(new Item('Mouse', 25));

console.log(`Total: $${cart.getTotal()}`);

The responsibilities are divided here: Cart manages the items, Item represents a product, and order.js orchestrates the interactions.

This separation ensures that each module is self-contained and easier to test and change independently.

? Encapsulation: Hide Implementation Details

One of the goals of modularity is encapsulation—hiding the internal workings of a module from the rest of the system.

External code should only interact with a module through its well-defined interface.

This makes changing the module’s internal implementation easier without affecting other parts of the system.

Example: Encapsulating Cart Logic

Let’s say we want to change how we calculate the total in the Cart. Maybe now we need to account for sales tax. We can encapsulate this logic inside the Cart class:

// cart.js

export class Cart {

constructor(taxRate) {

this.items = [];

this.taxRate = taxRate;

}

addItem(item) {

this.items.push(item);

}

getTotal() {

const total = this.items.reduce((sum, item) => sum + item.price, 0);

return total + total * this.taxRate;

}

}

// Now, the rest of the system does not need to know about tax calculations.

Other parts of the system (like order.js) are unaffected by changes in how the total is calculated. This makes your system more flexible and easier to maintain.

? Separation of Concerns: Keep Responsibilities Clear

A common problem in large systems is that different parts of the system get entangled.

When a module starts taking on too many responsibilities, it becomes harder to change or reuse in different contexts.

The separation of concerns principle ensures that each module has one specific responsibility.

Example: Handling Payment Separately

In the shopping cart example, payment processing should be handled in a separate module:

// payment.js

export class Payment {

static process(cart) {

const total = cart.getTotal();

console.log(`Processing payment of $${total}`);

// Payment logic goes here

}

}

// order.js

import { Cart } from './cart.js';

import { Payment } from './payment.js';

const cart = new Cart(0.07); // 7% tax rate

cart.addItem(new Item('Laptop', 1000));

cart.addItem(new Item('Mouse', 25));

Payment.process(cart);

Now, the payment logic is separated from cart management. This makes it easy to modify the payment process later (e.g., integrating with a different payment provider) without affecting the rest of the system.

? Testing Modules Independently

One of the greatest benefits of modularity is that you can test each module independently.

In the example above, you could write unit tests for the Cart class without needing to worry about how payments are processed.

Example: Unit Testing the Cart

// cart.test.js

import { Cart } from './cart.js';

import { Item } from './item.js';

test('calculates total with tax', () => {

const cart = new Cart(0.05); // 5% tax

cart.addItem(new Item('Book', 20));

expect(cart.getTotal()).toBe(21);

});

With a clear separation of concerns, each module can be tested in isolation, making debugging easier and development faster.

? Handling Dependencies: Avoid Tight Coupling

When modules depend too heavily on each other, changes in one part of the system can have unexpected consequences elsewhere.

To minimize this, aim for loose coupling between modules.

This allows each module to evolve independently.

Example: Injecting Dependencies

Instead of hardcoding dependencies inside a module, pass them in as arguments:

// cart.js

export class Cart {

constructor(taxRateCalculator) {

this.items = [];

this.taxRateCalculator = taxRateCalculator;

}

addItem(item) {

this.items.push(item);

}

getTotal() {

const total = this.items.reduce((sum, item) => sum + item.price, 0);

return total + this.taxRateCalculator(total);

}

}

This approach makes the Cart class more flexible and easier to test with different tax calculations.

Conclusion: Keep Systems Modular, Flexible, and Easy to Change

Happy Coding! ?

以上是Understanding Clean Code: Systems ⚡️的详细内容。更多信息请关注PHP中文网其他相关文章!

超越浏览器:现实世界中的JavaScriptApr 12, 2025 am 12:06 AM

超越浏览器:现实世界中的JavaScriptApr 12, 2025 am 12:06 AMJavaScript在现实世界中的应用包括服务器端编程、移动应用开发和物联网控制:1.通过Node.js实现服务器端编程,适用于高并发请求处理。2.通过ReactNative进行移动应用开发,支持跨平台部署。3.通过Johnny-Five库用于物联网设备控制,适用于硬件交互。

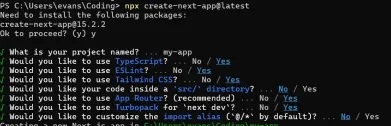

使用Next.js(后端集成)构建多租户SaaS应用程序Apr 11, 2025 am 08:23 AM

使用Next.js(后端集成)构建多租户SaaS应用程序Apr 11, 2025 am 08:23 AM我使用您的日常技术工具构建了功能性的多租户SaaS应用程序(一个Edtech应用程序),您可以做同样的事情。 首先,什么是多租户SaaS应用程序? 多租户SaaS应用程序可让您从唱歌中为多个客户提供服务

如何使用Next.js(前端集成)构建多租户SaaS应用程序Apr 11, 2025 am 08:22 AM

如何使用Next.js(前端集成)构建多租户SaaS应用程序Apr 11, 2025 am 08:22 AM本文展示了与许可证确保的后端的前端集成,并使用Next.js构建功能性Edtech SaaS应用程序。 前端获取用户权限以控制UI的可见性并确保API要求遵守角色库

JavaScript:探索网络语言的多功能性Apr 11, 2025 am 12:01 AM

JavaScript:探索网络语言的多功能性Apr 11, 2025 am 12:01 AMJavaScript是现代Web开发的核心语言,因其多样性和灵活性而广泛应用。1)前端开发:通过DOM操作和现代框架(如React、Vue.js、Angular)构建动态网页和单页面应用。2)服务器端开发:Node.js利用非阻塞I/O模型处理高并发和实时应用。3)移动和桌面应用开发:通过ReactNative和Electron实现跨平台开发,提高开发效率。

JavaScript的演变:当前的趋势和未来前景Apr 10, 2025 am 09:33 AM

JavaScript的演变:当前的趋势和未来前景Apr 10, 2025 am 09:33 AMJavaScript的最新趋势包括TypeScript的崛起、现代框架和库的流行以及WebAssembly的应用。未来前景涵盖更强大的类型系统、服务器端JavaScript的发展、人工智能和机器学习的扩展以及物联网和边缘计算的潜力。

神秘的JavaScript:它的作用以及为什么重要Apr 09, 2025 am 12:07 AM

神秘的JavaScript:它的作用以及为什么重要Apr 09, 2025 am 12:07 AMJavaScript是现代Web开发的基石,它的主要功能包括事件驱动编程、动态内容生成和异步编程。1)事件驱动编程允许网页根据用户操作动态变化。2)动态内容生成使得页面内容可以根据条件调整。3)异步编程确保用户界面不被阻塞。JavaScript广泛应用于网页交互、单页面应用和服务器端开发,极大地提升了用户体验和跨平台开发的灵活性。

Python还是JavaScript更好?Apr 06, 2025 am 12:14 AM

Python还是JavaScript更好?Apr 06, 2025 am 12:14 AMPython更适合数据科学和机器学习,JavaScript更适合前端和全栈开发。 1.Python以简洁语法和丰富库生态着称,适用于数据分析和Web开发。 2.JavaScript是前端开发核心,Node.js支持服务器端编程,适用于全栈开发。

如何安装JavaScript?Apr 05, 2025 am 12:16 AM

如何安装JavaScript?Apr 05, 2025 am 12:16 AMJavaScript不需要安装,因为它已内置于现代浏览器中。你只需文本编辑器和浏览器即可开始使用。1)在浏览器环境中,通过标签嵌入HTML文件中运行。2)在Node.js环境中,下载并安装Node.js后,通过命令行运行JavaScript文件。

热AI工具

Undresser.AI Undress

人工智能驱动的应用程序,用于创建逼真的裸体照片

AI Clothes Remover

用于从照片中去除衣服的在线人工智能工具。

Undress AI Tool

免费脱衣服图片

Clothoff.io

AI脱衣机

AI Hentai Generator

免费生成ai无尽的。

热门文章

热工具

EditPlus 中文破解版

体积小,语法高亮,不支持代码提示功能

记事本++7.3.1

好用且免费的代码编辑器

SecLists

SecLists是最终安全测试人员的伙伴。它是一个包含各种类型列表的集合,这些列表在安全评估过程中经常使用,都在一个地方。SecLists通过方便地提供安全测试人员可能需要的所有列表,帮助提高安全测试的效率和生产力。列表类型包括用户名、密码、URL、模糊测试有效载荷、敏感数据模式、Web shell等等。测试人员只需将此存储库拉到新的测试机上,他就可以访问到所需的每种类型的列表。

MinGW - 适用于 Windows 的极简 GNU

这个项目正在迁移到osdn.net/projects/mingw的过程中,你可以继续在那里关注我们。MinGW:GNU编译器集合(GCC)的本地Windows移植版本,可自由分发的导入库和用于构建本地Windows应用程序的头文件;包括对MSVC运行时的扩展,以支持C99功能。MinGW的所有软件都可以在64位Windows平台上运行。

ZendStudio 13.5.1 Mac

功能强大的PHP集成开发环境