Go 数组如何工作以及如何使用 For-Range

- WBOYWBOYWBOYWBOYWBOYWBOYWBOYWBOYWBOYWBOYWBOYWBOYWB原创

- 2024-08-20 18:44:00410浏览

这是帖子的摘录;完整的帖子可以在这里找到:Go 数组如何工作以及如何使用 For-Range 进行技巧。

经典的 Golang 数组和切片非常简单。数组是固定大小的,而切片是动态的。但我必须告诉你,Go 表面上看起来很简单,但它背后却发生了很多事情。

一如既往,我们将从基础知识开始,然后进行更深入的研究。别担心,当你从不同的角度观察数组时,它们会变得非常有趣。

我们将在下一部分中覆盖切片,一旦准备好我就会把它放在这里。

什么是数组?

Go 中的数组与其他编程语言中的数组非常相似。它们有固定的大小,并将相同类型的元素存储在连续的内存位置。

这意味着 Go 可以快速访问每个元素,因为它们的地址是根据数组的起始地址和元素的索引计算的。

func main() {

arr := [5]byte{0, 1, 2, 3, 4}

println("arr", &arr)

for i := range arr {

println(i, &arr[i])

}

}

// Output:

// arr 0x1400005072b

// 0 0x1400005072b

// 1 0x1400005072c

// 2 0x1400005072d

// 3 0x1400005072e

// 4 0x1400005072f

这里有几件事需要注意:

- 数组arr的地址与第一个元素的地址相同。

- 每个元素的地址彼此相距 1 个字节,因为我们的元素类型是 byte。

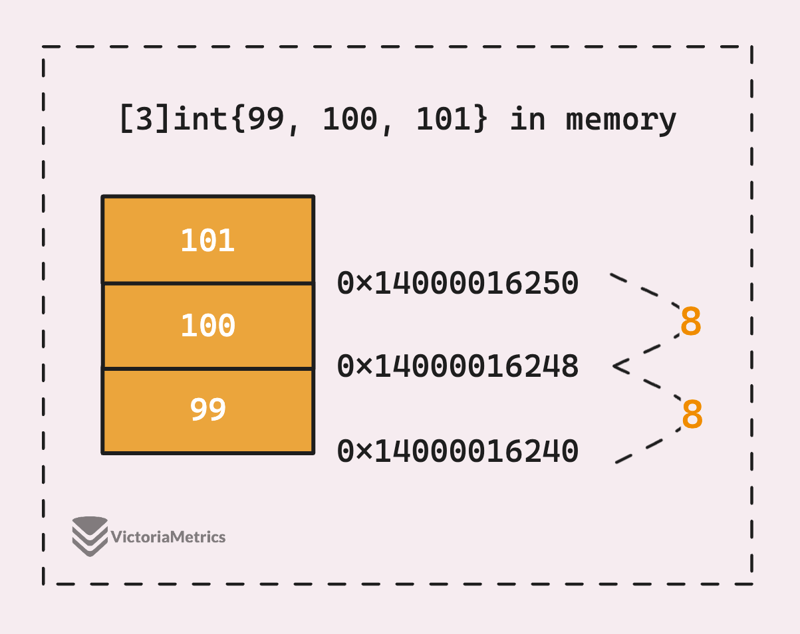

仔细看图片。

我们的堆栈是从较高的地址向下增长到较低的地址,对吧?这张图准确地展示了数组在栈中的样子,从 arr[4] 到 arr[0]。

那么,这是否意味着我们可以通过知道第一个元素(或数组)的地址和元素的大小来访问数组的任何元素?让我们用 int 数组和不安全的包来尝试一下:

func main() {

a := [3]int{99, 100, 101}

p := unsafe.Pointer(&a[0])

a1 := unsafe.Pointer(uintptr(p) + 8)

a2 := unsafe.Pointer(uintptr(p) + 16)

fmt.Println(*(*int)(p))

fmt.Println(*(*int)(a1))

fmt.Println(*(*int)(a2))

}

// Output:

// 99

// 100

// 101

好吧,我们获取指向第一个元素的指针,然后通过将 int 大小的倍数相加来计算指向下一个元素的指针,在 64 位架构上,int 大小为 8 个字节。然后我们使用这些指针来访问并将它们转换回 int 值。

该示例只是为了教育目的而使用 unsafe 包直接访问内存。在不了解后果的情况下,不要在生产中这样做。

现在,类型 T 的数组本身并不是一种类型,但是具有 特定大小和类型 T 的数组被视为一种类型。这就是我的意思:

func main() {

a := [5]byte{}

b := [4]byte{}

fmt.Printf("%T\n", a) // [5]uint8

fmt.Printf("%T\n", b) // [4]uint8

// cannot use b (variable of type [4]byte) as [5]byte value in assignment

a = b

}

尽管 a 和 b 都是字节数组,Go 编译器将它们视为完全不同的类型,%T 格式清楚地表明了这一点。

这是 Go 编译器在内部如何看待它的 (src/cmd/compile/internal/types2/array.go):

// An Array represents an array type.

type Array struct {

len int64

elem Type

}

// NewArray returns a new array type for the given element type and length.

// A negative length indicates an unknown length.

func NewArray(elem Type, len int64) *Array { return &Array{len: len, elem: elem} }

数组的长度在类型本身中“编码”,因此编译器从其类型知道数组的长度。尝试将一种大小的数组分配给另一种大小的数组或比较它们,将导致类型不匹配错误。

数组文字

Go 中初始化数组的方法有很多种,有些在实际项目中可能很少用到:

var arr1 [10]int // [0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0]

// With value, infer-length

arr2 := [...]int{1, 2, 3, 4, 5} // [1 2 3 4 5]

// With index, infer-length

arr3 := [...]int{11: 3} // [0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 3]

// Combined index and value

arr4 := [5]int{1, 4: 5} // [1 0 0 0 5]

arr5 := [5]int{2: 3, 4, 4: 5} // [0 0 3 4 5]

我们上面所做的(除了第一个)是定义和初始化它们的值,这称为“复合文字”。该术语也用于切片、映射和结构。

现在,有一件有趣的事情:当我们创建一个少于 4 个元素的数组时,Go 会生成指令将值逐个放入数组中。

所以当我们执行 arr := [3]int{1, 2, 3, 4} 时,实际发生的是:

arr := [4]int{}

arr[0] = 1

arr[1] = 2

arr[2] = 3

arr[3] = 4

这种策略称为本地代码初始化。这意味着初始化代码是在特定函数的范围内生成和执行的,而不是全局或静态初始化代码的一部分。

当你阅读下面的另一个初始化策略时,你会变得更清楚,其中的值并不是像那样一个一个地放入数组中。

“超过 4 个元素的数组怎么样?”

编译器在二进制文件中创建数组的静态表示,这称为“静态初始化”策略。

This means the values of the array elements are stored in a read-only section of the binary. This static data is created at compile time, so the values are directly embedded into the binary. If you're curious how [5]int{1,2,3,4,5} looks like in Go assembly:

main..stmp_1 SRODATA static size=40

0x0000 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 02 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

0x0010 03 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 04 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

0x0020 05 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ........

It's not easy to see the value of the array, we can still get some key info from this.

Our data is stored in stmp_1, which is read-only static data with a size of 40 bytes (8 bytes for each element), and the address of this data is hardcoded in the binary.

The compiler generates code to reference this static data. When our application runs, it can directly use this pre-initialized data without needing additional code to set up the array.

const readonly = [5]int{1, 2, 3, 4, 5}

arr := readonly

"What about an array with 5 elements but only 3 of them initialized?"

Good question, this literal [5]int{1,2,3} falls into the first category, where Go puts the value into the array one by one.

While talking about defining and initializing arrays, we should mention that not every array is allocated on the stack. If it's too big, it gets moved to the heap.

But how big is "too big," you might ask.

As of Go 1.23, if the size of the variable, not just array, exceeds a constant value MaxStackVarSize, which is currently 10 MB, it will be considered too large for stack allocation and will escape to the heap.

func main() {

a := [10 * 1024 * 1024]byte{}

println(&a)

b := [10*1024*1024 + 1]byte{}

println(&b)

}

In this scenario, b will move to the heap while a won't.

Array operations

The length of the array is encoded in the type itself. Even though arrays don't have a cap property, we can still get it:

func main() {

a := [5]int{1, 2, 3}

println(len(a)) // 5

println(cap(a)) // 5

}

The capacity equals the length, no doubt, but the most important thing is that we know this at compile time, right?

So len(a) doesn't make sense to the compiler because it's not a runtime property, Go compiler knows the value at compile time.

...

This is an excerpt of the post; the full post is available here: How Go Arrays Work and Get Tricky with For-Range.

以上是Go 数组如何工作以及如何使用 For-Range的详细内容。更多信息请关注PHP中文网其他相关文章!