Rumah >hujung hadapan web >tutorial js >Menguasai Prinsip SOLID dalam React Native dan MERN Stack

Menguasai Prinsip SOLID dalam React Native dan MERN Stack

- WBOYasal

- 2024-09-03 15:23:01947semak imbas

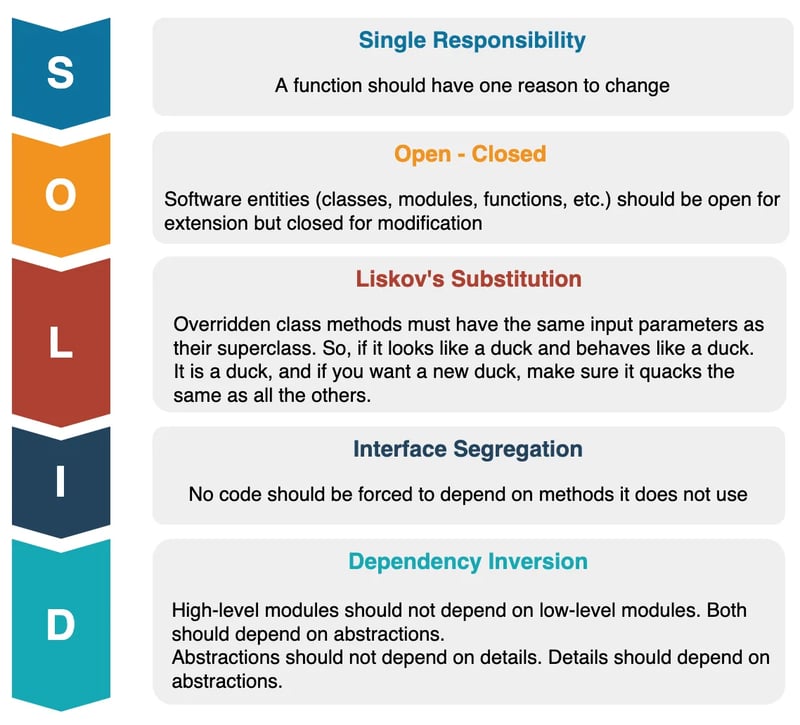

Prinsip SOLID, yang diperkenalkan oleh Robert C. Martin (Uncle Bob), membentuk asas reka bentuk perisian yang baik. Prinsip ini membimbing pembangun dalam mencipta sistem yang boleh diselenggara, berskala dan mudah difahami. Dalam blog ini, kami akan mendalami setiap prinsip SOLID dan meneroka cara ia boleh digunakan dalam konteks React Native dan timbunan MERN (MongoDB, Express.js, React, Node.js).

1. Prinsip Tanggungjawab Tunggal (SRP)

Definisi: Kelas sepatutnya hanya mempunyai satu sebab untuk berubah, bermakna ia hanya perlu mempunyai satu pekerjaan atau tanggungjawab.

Penjelasan:

Prinsip Tanggungjawab Tunggal (SRP) memastikan bahawa kelas atau modul difokuskan pada satu aspek kefungsian perisian. Apabila kelas mempunyai lebih daripada satu tanggungjawab, perubahan yang berkaitan dengan satu tanggungjawab secara tidak sengaja boleh memberi kesan kepada yang lain, membawa kepada pepijat dan kos penyelenggaraan yang lebih tinggi.

Contoh Asli Bertindak Balas:

Pertimbangkan komponen UserProfile dalam aplikasi React Native. Pada mulanya, komponen ini mungkin bertanggungjawab untuk kedua-dua memaparkan antara muka pengguna dan mengendalikan permintaan API untuk mengemas kini data pengguna. Ini melanggar SRP kerana komponen melakukan dua perkara berbeza: mengurus UI dan logik perniagaan.

Pelanggaran:

const UserProfile = ({ userId }) => {

const [userData, setUserData] = useState(null);

useEffect(() => {

fetch(`/api/users/${userId}`)

.then(response => response.json())

.then(data => setUserData(data));

}, [userId]);

return (

<View>

<Text>{userData?.name}</Text>

<Text>{userData?.email}</Text>

</View>

);

};

Dalam contoh ini, komponen UserProfile bertanggungjawab untuk mengambil data dan memberikan UI. Jika anda perlu menukar cara data diambil (cth., dengan menggunakan titik akhir API yang berbeza atau memperkenalkan caching), anda perlu mengubah suai komponen, yang boleh membawa kepada kesan sampingan yang tidak diingini dalam UI.

Refactor:

Untuk mematuhi SRP, pisahkan logik pengambilan data daripada logik pemaparan UI.

// Custom hook for fetching user data

const useUserData = (userId) => {

const [userData, setUserData] = useState(null);

useEffect(() => {

const fetchUserData = async () => {

const response = await fetch(`/api/users/${userId}`);

const data = await response.json();

setUserData(data);

};

fetchUserData();

}, [userId]);

return userData;

};

// UserProfile component focuses only on rendering the UI

const UserProfile = ({ userId }) => {

const userData = useUserData(userId);

return (

<View>

<Text>{userData?.name}</Text>

<Text>{userData?.email}</Text>

</View>

);

};

Dalam refactor ini, cangkuk useUserData mengendalikan pengambilan data, membenarkan komponen UserProfile menumpukan semata-mata pada pemaparan UI. Sekarang, jika anda perlu mengubah suai logik pengambilan data, anda boleh melakukannya tanpa menjejaskan kod UI.

Contoh Node.js:

Bayangkan UserController yang mengendalikan kedua-dua pertanyaan pangkalan data dan logik perniagaan dalam aplikasi Node.js. Ini melanggar SRP kerana pengawal mempunyai pelbagai tanggungjawab.

Pelanggaran:

class UserController {

async getUserProfile(req, res) {

const user = await db.query('SELECT * FROM users WHERE id = ?', [req.params.id]);

res.json(user);

}

async updateUserProfile(req, res) {

const result = await db.query('UPDATE users SET name = ? WHERE id = ?', [req.body.name, req.params.id]);

res.json(result);

}

}

Di sini, UserController bertanggungjawab untuk berinteraksi dengan pangkalan data dan mengendalikan permintaan HTTP. Sebarang perubahan dalam logik interaksi pangkalan data memerlukan pengubahsuaian dalam pengawal, meningkatkan risiko pepijat.

Refactor:

Pisahkan logik interaksi pangkalan data ke dalam kelas repositori, membenarkan pengawal menumpukan pada pengendalian permintaan HTTP.

// UserRepository class handles data access logic

class UserRepository {

async getUserById(id) {

return db.query('SELECT * FROM users WHERE id = ?', [id]);

}

async updateUser(id, name) {

return db.query('UPDATE users SET name = ? WHERE id = ?', [name, id]);

}

}

// UserController focuses on business logic and HTTP request handling

class UserController {

constructor(userRepository) {

this.userRepository = userRepository;

}

async getUserProfile(req, res) {

const user = await this.userRepository.getUserById(req.params.id);

res.json(user);

}

async updateUserProfile(req, res) {

const result = await this.userRepository.updateUser(req.params.id, req.body.name);

res.json(result);

}

}

Kini, UserController tertumpu pada pengendalian permintaan HTTP dan logik perniagaan, manakala UserRepository bertanggungjawab untuk interaksi pangkalan data. Pemisahan ini menjadikan kod lebih mudah untuk diselenggara dan dilanjutkan.

2. Prinsip Terbuka/Tertutup (OCP)

Definisi: Entiti perisian harus dibuka untuk sambungan tetapi ditutup untuk pengubahsuaian.

Penjelasan:

Prinsip Terbuka/Tertutup (OCP) menekankan bahawa kelas, modul dan fungsi harus mudah dilanjutkan tanpa mengubah suai kod sedia ada. Ini menggalakkan penggunaan abstraksi dan antara muka, membolehkan pembangun memperkenalkan fungsi baharu dengan risiko minimum untuk memperkenalkan pepijat dalam kod sedia ada.

Contoh Asli Bertindak Balas:

Bayangkan komponen butang yang pada mulanya mempunyai gaya tetap. Apabila aplikasi berkembang, anda perlu memanjangkan butang dengan gaya yang berbeza untuk pelbagai kes penggunaan. Jika anda terus mengubah suai komponen sedia ada setiap kali anda memerlukan gaya baharu, akhirnya anda akan melanggar OCP.

Pelanggaran:

const Button = ({ onPress, type, children }) => {

let style = {};

if (type === 'primary') {

style = { backgroundColor: 'blue', color: 'white' };

} else if (type === 'secondary') {

style = { backgroundColor: 'gray', color: 'black' };

}

return (

<TouchableOpacity onPress={onPress} style={style}>

<Text>{children}</Text>

</TouchableOpacity>

);

};

Dalam contoh ini, komponen Butang perlu diubah suai setiap kali jenis butang baharu ditambah. Ini tidak berskala dan meningkatkan risiko pepijat.

Refactor:

Faktorkan semula komponen Butang untuk dibuka untuk sambungan dengan membenarkan gaya dihantar masuk sebagai prop.

const Button = ({ onPress, style, children }) => {

const defaultStyle = {

padding: 10,

borderRadius: 5,

};

return (

<TouchableOpacity onPress={onPress} style={[defaultStyle, style]}>

<Text>{children}</Text>

</TouchableOpacity>

);

};

// Now, you can extend the button's style without modifying the component itself

<Button style={{ backgroundColor: 'blue', color: 'white' }} onPress={handlePress}>

Primary Button

</Button>

<Button style={{ backgroundColor: 'gray', color: 'black' }} onPress={handlePress}>

Secondary Button

</Button>

Dengan pemfaktoran semula, komponen Butang ditutup untuk pengubahsuaian tetapi dibuka untuk sambungan, membenarkan gaya butang baharu ditambah tanpa mengubah logik dalaman komponen.

Contoh Node.js:

Pertimbangkan sistem pemprosesan pembayaran dalam aplikasi Node.js yang menyokong berbilang kaedah pembayaran. Pada mulanya, anda mungkin tergoda untuk mengendalikan setiap kaedah pembayaran dalam satu kelas.

Pelanggaran:

class PaymentProcessor {

processPayment(amount, method) {

if (method === 'paypal') {

console.log(`Paid ${amount} using PayPal`);

} else if (method === 'stripe') {

console.log(`Paid ${amount} using Stripe`);

} else if (method === 'creditcard') {

console.log(`Paid ${amount} using Credit Card`);

}

}

}

Dalam contoh ini, menambah kaedah pembayaran baharu memerlukan pengubahsuaian kelas PaymentProcessor, melanggar OCP.

Refactor:

Introduce a strategy pattern to encapsulate each payment method in its own class, making the PaymentProcessor open for extension but closed for modification.

class PaymentProcessor {

constructor(paymentMethod) {

this.paymentMethod = paymentMethod;

}

processPayment(amount) {

return this.paymentMethod.pay(amount);

}

}

// Payment methods encapsulated in their own classes

class PayPalPayment {

pay(amount) {

console.log(`Paid ${amount} using PayPal`);

}

}

class StripePayment {

pay(amount) {

console.log(`Paid ${amount} using Stripe`);

}

}

class CreditCardPayment {

pay(amount) {

console.log(`Paid ${amount} using Credit Card`);

}

}

// Usage

const paypalProcessor = new PaymentProcessor(new PayPalPayment());

paypalProcessor.processPayment(100);

const stripeProcessor = new PaymentProcessor(new StripePayment());

stripeProcessor.processPayment(200);

Now, to add a new payment method, you simply create a new class without modifying the existing PaymentProcessor. This adheres to OCP and makes the system more scalable and maintainable.

3. Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP)

Definition: Objects of a superclass should be replaceable with objects of a subclass without affecting the correctness of the program.

Explanation:

The Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP) ensures that subclasses can stand in for their parent classes without causing errors or altering the

expected behavior. This principle helps maintain the integrity of a system's design and ensures that inheritance is used appropriately.

React Native Example:

Imagine a base Shape class with a method draw. You might have several subclasses like Circle and Square, each with its own implementation of the draw method. These subclasses should be able to replace Shape without causing issues.

Correct Implementation:

class Shape {

draw() {

// Default drawing logic

}

}

class Circle extends Shape {

draw() {

super.draw();

// Circle-specific drawing logic

}

}

class Square extends Shape {

draw() {

super.draw();

// Square-specific drawing logic

}

}

function renderShape(shape) {

shape.draw();

}

// Both Circle and Square can replace Shape without issues

const circle = new Circle();

renderShape(circle);

const square = new Square();

renderShape(square);

In this example, both Circle and Square classes can replace the Shape class without causing any problems, adhering to LSP.

Node.js Example:

Consider a base Bird class with a method fly. You might have a subclass Sparrow that extends Bird and provides its own implementation of fly. However, if you introduce a subclass like Penguin that cannot fly, it violates LSP.

Violation:

class Bird {

fly() {

console.log('Flying');

}

}

class Sparrow extends Bird {

fly() {

super.fly();

console.log('Sparrow flying');

}

}

class Penguin extends Bird {

fly() {

throw new Error("Penguins can't fly");

}

}

In this example, substituting a Penguin for a Bird will cause errors, violating LSP.

Refactor:

Instead of extending Bird, you can create a different hierarchy or use composition to avoid violating LSP.

class Bird {

layEggs() {

console.log('Laying eggs');

}

}

class FlyingBird extends Bird {

fly() {

console.log('Flying');

}

}

class Penguin extends Bird {

swim() {

console.log('Swimming');

}

}

// Now, Penguin does not extend Bird in a way that violates LSP

In this refactor, Penguin no longer extends Bird in a way that requires it to support flying, adhering to LSP.

4. Interface Segregation Principle (ISP)

Definition: A client should not be forced to implement interfaces it doesn't use.

Explanation:

The Interface Segregation Principle (ISP) suggests that instead of having large, monolithic interfaces, it's better to have smaller, more specific interfaces. This way, classes implementing the interfaces are only required to implement the methods they actually use, making the system more flexible and easier to maintain.

React Native Example:

Suppose you have a UserActions interface that includes methods for both regular users and admins. This forces regular users to implement admin-specific methods, which they don't need, violating ISP.

Violation:

interface UserActions {

viewProfile(): void;

deleteUser(): void;

}

class RegularUser implements UserActions {

viewProfile() {

console.log('Viewing profile');

}

deleteUser() {

throw new Error("Regular users can't delete users");

}

}

In this example, the RegularUser class is forced to implement a method (deleteUser) it doesn't need, violating ISP.

Refactor:

Split the UserActions interface into more specific interfaces for regular users and admins.

interface RegularUserActions {

viewProfile(): void;

}

interface AdminUserActions extends RegularUserActions {

deleteUser(): void;

}

class RegularUser implements RegularUserActions {

viewProfile() {

console.log('Viewing profile');

}

}

class AdminUser implements AdminUserActions {

viewProfile() {

console.log('Viewing profile');

}

deleteUser() {

console.log('User deleted');

}

}

Now, RegularUser only implements the methods it needs, adhering to ISP. Admin users implement the AdminUserActions interface, which extends RegularUserActions, ensuring that they have access to both sets of methods.

Node.js Example:

Consider a logger interface that forces implementing methods for various log levels, even if they are not required.

Violation:

class Logger {

logError(message) {

console.error(message);

}

logInfo(message) {

console.log(message);

}

logDebug(message) {

console.debug(message);

}

}

class ErrorLogger extends Logger {

logError(message) {

console.error(message);

}

logInfo(message) {

// Not needed, but must be implemented

}

logDebug(message) {

// Not needed, but must be implemented

}

}

In this example, ErrorLogger is forced to implement methods (logInfo, logDebug) it doesn't need, violating ISP.

Refactor:

Create smaller, more specific interfaces to allow classes to implement only what they need.

class ErrorLogger {

logError(message) {

console.error(message);

}

}

class InfoLogger {

logInfo(message) {

console.log(message);

}

}

class DebugLogger {

logDebug(message) {

console.debug(message);

}

}

Now, classes can implement only the logging methods they need, adhering to ISP and making the system more modular.

5. Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP)

Definition: High-level modules should not depend on low-level modules. Both should depend on abstractions.

Explanation:

The Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP) emphasizes that high-level modules (business logic) should not be directly dependent on low-level modules (e.g., database access, external services). Instead, both should depend on abstractions, such as interfaces. This makes the system more flexible and easier to modify or extend.

React Native Example:

In a React Native application, you might have a UserProfile component that directly fetches data from an API service. This creates a tight coupling between the component and the specific API implementation, violating DIP.

Violation:

const UserProfile = ({ userId }) => {

const [userData, setUserData] = useState(null);

useEffect(() => {

fetch(`/api/users/${userId}`)

.then(response => response.json())

.then(data => setUserData(data));

}, [userId]);

return (

<View>

<Text>{userData?.name}</Text>

<Text>{userData?.email}</Text>

</View>

);

};

In this example, the UserProfile component is tightly coupled with a specific API implementation. If the API changes, the component must be modified, violating DIP.

Refactor:

Introduce an abstraction layer (such as a service) that handles data fetching. The UserProfile component will depend on this abstraction, not the concrete implementation.

// Define an abstraction (interface)

const useUserData = (userId, apiService) => {

const [userData, setUserData] = useState(null);

useEffect(() => {

apiService.getUserById(userId).then(setUserData);

}, [userId]);

return userData;

};

// UserProfile depends on an abstraction, not a specific API implementation

const UserProfile = ({ userId, apiService }) => {

const userData = useUserData(userId, apiService);

return (

<View>

<Text>{userData?.name}</Text>

<Text>{userData?.email}</Text>

</View>

);

};

Now, UserProfile can work with any service that conforms to the apiService interface, adhering to DIP and making the code more flexible.

Node.js Example:

In a Node.js application, you might have a service that directly uses a specific database implementation. This creates a tight coupling between the service and the database, violating DIP.

Violation:

class UserService {

getUserById(id) {

return db.query('SELECT * FROM users WHERE id = ?', [id]);

}

}

In this example, UserService is tightly coupled with the specific database implementation (db.query). If you want to switch databases, you must modify UserService, violating DIP.

Refactor:

Introduce an abstraction (interface) for database access, and have UserService depend on this abstraction instead of the concrete implementation.

// Define an abstraction (interface)

class UserRepository {

constructor(database) {

this.database = database;

}

getUserById(id) {

return this.database.findById(id);

}

}

// Now, UserService depends on an abstraction, not a specific database implementation

class UserService {

constructor(userRepository) {

this.userRepository = userRepository;

}

async getUserById(id) {

return this.userRepository.getUserById(id);

}

}

// You can easily switch database implementations without modifying UserService

const mongoDatabase = new MongoDatabase();

const userRepository = new UserRepository(mongoDatabase);

const userService = new UserService(userRepository);

By depending on an abstraction (UserRepository), UserService is no longer tied to a specific database implementation. This adheres to DIP, making the system more flexible and easier to maintain.

Conclusion

The SOLID principles are powerful guidelines that help developers create more maintainable, scalable, and robust software systems. By applying these principles in your React

Native and MERN stack projects, you can write cleaner code that's easier to understand, extend, and modify.

Understanding and implementing SOLID principles might require a bit of effort initially, but the long-term benefits—such as reduced technical debt, easier code maintenance, and more flexible systems—are well worth it. Start applying these principles in your projects today, and you'll soon see the difference they can make!

Atas ialah kandungan terperinci Menguasai Prinsip SOLID dalam React Native dan MERN Stack. Untuk maklumat lanjut, sila ikut artikel berkaitan lain di laman web China PHP!

Artikel berkaitan

Lihat lagi- Analisis mendalam bagi komponen kumpulan senarai Bootstrap

- Penjelasan terperinci tentang fungsi JavaScript kari

- Contoh lengkap penjanaan kata laluan JS dan pengesanan kekuatan (dengan muat turun kod sumber demo)

- Angularjs menyepadukan UI WeChat (weui)

- Cara cepat bertukar antara Cina Tradisional dan Cina Ringkas dengan JavaScript dan helah untuk tapak web menyokong pertukaran antara kemahiran_javascript Cina Ringkas dan Tradisional