Maison >développement back-end >Tutoriel Python >Créez un tableau de bord de statistiques GitHub en temps réel avec Python

Créez un tableau de bord de statistiques GitHub en temps réel avec Python

- 王林original

- 2024-08-27 06:04:06683parcourir

Utilisez l'API GitHub Firehose pour visualiser les utilisateurs GitHub les plus actifs en temps réel

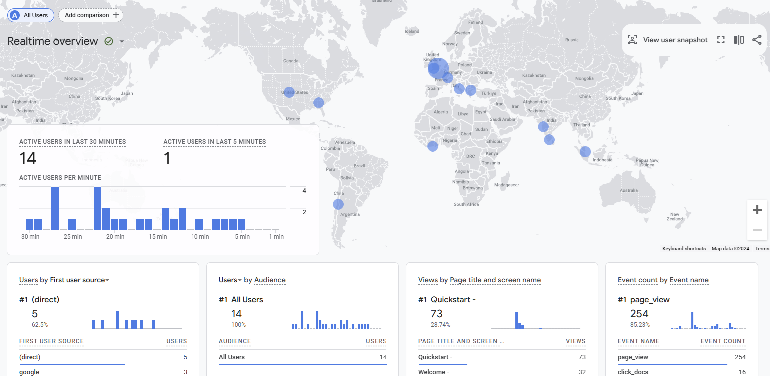

Avez-vous déjà essayé le tableau de bord en temps réel dans Google Analytics ? C’est assez fascinant de voir les gens interagir avec votre site Web en temps réel. Saviez-vous que vous pouvez créer quelque chose de similaire en utilisant le timelime de GitHub ?

Il est étonnamment facile de construire un prototype de base dans Streamlit. J'aimerais vous montrer comment créer une version MVP très modeste et minimale d'un tableau de bord en temps réel. Vous pouvez utiliser le flux public des événements GitHub, à savoir : The GitHub Firehose.

Vous pouvez l'utiliser pour créer un pipeline et un tableau de bord très simples qui suivent le nombre d'événements par nom d'utilisateur GitHub et vous montrent le top 10 actuel.

Voici un aperçu de la charge utile que vous obtenez de l'API GithubFirehose. Dans ce tutoriel, nous allons n'en utiliser qu'une petite partie (l'objet "acteur")

{

"id": "41339742815",

"type": "WatchEvent",

"actor": {

"id": 12345678,

"login": "someuser123",

"display_login": "someuser123",

"gravatar_id": "",

"url": "https://api.github.com/users/someuser123",

"avatar_url": "https://avatars.githubusercontent.com/u/12345678?",

},

"repo": {

"id": 89012345,

"name": "someorg/somerepo",

"url": "https://api.github.com/repos/someorg/somerepo",

},

"payload": {

"action": "started"

},

"public": true,

"created_at": "2024-08-26T12:21:53Z"

}

Mais nous ne pouvons pas simplement connecter le Firehose à Streamlit, nous avons d'abord besoin d'un back-end pour traiter les données. Pourquoi ?

Le rendu des données en temps réel dans Streamlit peut être un défi

Streamlit est un outil fantastique pour créer rapidement des prototypes d'applications interactives avec Python. Cependant, lorsqu'il s'agit de restituer des données en temps réel, Streamlit peut s'avérer un peu délicat. Vous pouvez diffuser le GitHub Firehose dans Kafka assez facilement (mon collègue Kris Jenkins a un excellent tutoriel à ce sujet appelé High Performance Kafka Producers in Python)

Mais demander à Streamlit de restituer les données que vous consommez directement à partir de Kafka peut être une sorte de galère. Streamlit n'a pas été conçu pour gérer un flux continu de données circulant à chaque milliseconde. De toute façon, vous n’avez pas vraiment besoin que la visualisation soit actualisée à cette fréquence.

Même si votre flux de données source est mis à jour toutes les millisecondes (comme un journal de serveur très chargé), vous pouvez simplement afficher un instantané des données toutes les secondes. Pour ce faire, vous devez transférer ces données dans une base de données et les placer derrière une API que Streamlit peut interroger à un rythme plus gérable.

En plaçant les données derrière une API, vous facilitez non seulement la gestion par Streamlit, mais vous rendez également les données accessibles à d'autres outils. Cette approche nécessite un peu de développement backend, mais ne vous inquiétez pas — J'ai préparé un ensemble de conteneurs Docker et un fichier de composition Docker pour vous aider à démarrer localement.

Vous pouvez être un novice complet en back-end tout en comprenant comment cela fonctionne, je le promets.

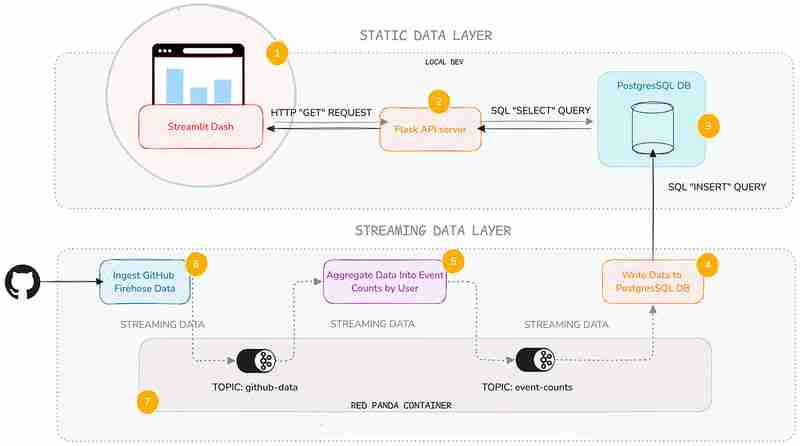

L'Architecture

Voici un aperçu rapide des composants que nous utiliserons :

Oui, je sais que cela ressemble à beaucoup, mais je vais me concentrer sur la couche de données statiques — à savoir le service API et le tableau de bord Streamlit. Je ne vais pas plonger ici dans les profondeurs obscures de la couche de données en streaming (mais je vais vous donner quelques liens au cas où vous voudriez en savoir plus).

J'ai ajouté cette couche car il est pratique de savoir comment fonctionnent généralement les back-ends de streaming, même si vous n'avez pas à les maintenir vous-même.

Voici une très brève description de ce que fait chaque service :

| Service | Description |

|---|---|

| Streamlit Service | Displays a Streamlit Dashboard which polls the API and renders the data in a chart and table. |

| Flask API | Serves a minimal REST API that can query a database and return the results as JSON. |

| Postgres Database | Stores the event count data. |

| Postgres Writer Service | Reads from a topic and continuously updates the database with new data. |

| Aggregation Service | Refines the raw event logs and continuously aggregates them into event counts broken down by GitHub display name. |

| Streaming Data Producer | Reads from a real-time public feed of activity on GitHub and streams the data to a topic in Redpanda (our local message broker). |

| Red Panda Server | Manages the flow of streaming data via topics (buffers for streaming data). |

You can inspect the code in the accompanying Github repo. Each service has its own subfolder, with code and a README:

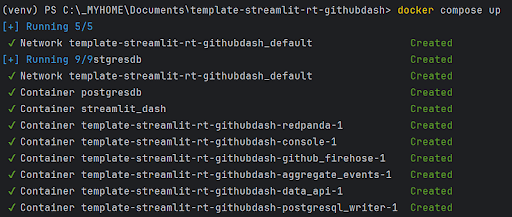

Setting Up Your Environment

To get started, you’ll need Docker with Docker Compose installed (and Git of course). The easiest way is to install Docker Desktop. Once you have Docker set up, follow these steps:

1. Clone the repository:

git clone https://github.com/quixio/template-streamlit-rt-githubdash

2. Navigate to the repository:

cd template-streamlit-rt-githubdash

3. Spin up the Containers:

docker compose up

You should see some log entries that look like this (make sure Docker Desktop is running).

4. Visit the Streamlit URL

Open your browser and go to http://localhost:8031. You should see your dashboard running.

Code explanation

Let’s take a look at the two main components of the static data layer: the dashboard and the data API.

The Streamlit Dashboard

Now, let’s look at how the Streamlit app uses this API. It polls the API, gets the results back as JSON, turns the JSON into a dataframe, then caches the results. To refresh the results, the cache is cleared at a defined interval (currently 1 second) so that Streamlit needs to retrieve the data again.

import streamlit as st

import requests

import time

import pandas as pd

import os

import logging

from datetime import datetime

import plotly.express as px

from dotenv import load_dotenv

load_dotenv() ### for local dev, outside of docker, load env vars from a .env file

logging.basicConfig(level=logging.INFO)

logger = logging.getLogger(__name__)

# API endpoint URL

api_url = os.environ['API_URL']

## Function to get data from the API

def get_data():

print(f"[{datetime.now()}] Fetching data from API...")

response = requests.get(api_url)

data = response.json()

df = pd.DataFrame(data)

try:

# Reorder columns

# df = df[['page_id', 'count']]

df = df[['displayname', 'event_count']]

except:

logger.info("No data yet...")

return df

# Function to get data and cache it

@st.cache_data

def get_cached_data():

return get_data()

# Streamlit UI

st.title("Real-time Dashboard for GitHub Data using Streamlit,Flask and Quix")

st.markdown("This dashboard reads from a table via an API, which is being continuously updated by a Quix Streams sink process running in Docker. It then displays a dynamically updating Plotly chart and table underneath.")

st.markdown("In the backend, there are services that:\n * Read from the GitHub Firehose \n * Stream the event data to Redpanda\n * Read from Redpanda and aggregate the events per GitHub user\n * Sinking the page event counts (which are continuously updating) to PostGres\n\n ")

st.markdown("Take a closer a look at the [back-end code](https://github.com/quixio/template-streamlit-rt-githubdash), and learn how to read from a real-time source and apply some kind of transformation to the data before bringing it into Streamlit (using only Python)")

# Placeholder for the bar chart and table

chart_placeholder = st.empty()

table_placeholder = st.empty()

# Placeholder for countdown text

countdown_placeholder = st.empty()

# Main loop

while True:

# Get the data

df = get_cached_data()

# Check that data is being retrieved and passed correctly

if df.empty:

st.error("No data found. Please check your data source.")

break

# Calculate dynamic min and max scales

min_count = df['event_count'].min()

max_count = df['event_count'].max()

min_scale = min_count * 0.99

max_scale = max_count * 1.01

# Create a Plotly figure

fig = px.bar(df, x='displayname', y='event_count', title="Current Top 10 active GitHub Users by event count",

range_y=[min_scale, max_scale])

# Style the chart

fig.update_layout(

xaxis_title="Display Name",

yaxis_title="Event Count",

xaxis=dict(tickangle=-90) # Vertical label orientation

)

# Display the Plotly chart in Streamlit using st.plotly_chart

chart_placeholder.plotly_chart(fig, use_container_width=True)

# Display the dataframe as a table

table_placeholder.table(df)

# Countdown

for i in range(1, 0, -1):

countdown_placeholder.text(f"Refreshing in {i} seconds...")

time.sleep(1)

# Clear the countdown text

countdown_placeholder.empty()

# Clear the cache to fetch new data

get_cached_data.clear()

This Streamlit app polls the API every second to fetch the latest data. It then displays this data in a dynamically updating bar chart and table. The @st.cache_data decorator is used to cache the data, reducing the load on the API.

The Data API

The API, built with Flask, serves as the gateway to our data. This code sets up a simple Flask API that queries a PostgreSQL database and returns the results as JSON. We’re using the psycopg2 library to interact with the database and Flask to define an API route.

import os

from flask import Flask, jsonify

from waitress import serve

import psycopg2

import logging

from dotenv import load_dotenv

load_dotenv() ### for local dev, outside of docker, load env vars from a .env file

logging.basicConfig(level=logging.INFO)

logger = logging.getLogger(__name__)

app = Flask(__name__)

# Replace with your PostgreSQL connection details

pg_host = os.environ['PG_HOST']

pg_port = os.getenv('PG_PORT','5432')

pg_db = os.environ['PG_DATABASE']

pg_user = os.environ['PG_USER']

pg_password = os.environ['PG_PASSWORD']

pg_table = os.environ['PG_TABLE']

# Establish a connection to PostgreSQL

conn = psycopg2.connect(

host=pg_host,

port=pg_port,

database=pg_db,

user=pg_user,

password=pg_password

)

@app.route('/events', methods=['GET'])

def get_user_events():

query = f"SELECT * FROM {pg_table} ORDER BY event_count DESC LIMIT 10"

logger.info(f"Running query: {query}")

try:

# Execute the query

with conn.cursor() as cursor:

cursor.execute(query)

results = cursor.fetchall()

columns = [desc[0] for desc in cursor.description]

# Convert the result to a list of dictionaries

results_list = [dict(zip(columns, row)) for row in results]

except:

logger.info(f"Error querying Postgres...")

results_list = [{"error": "Database probably not ready yet."}]

return jsonify(results_list)

if __name__ == '__main__':

serve(app, host="0.0.0.0", port=80)

You can set up a much fancier API with query parameters and whatnot, but here I want to keep it simple. When an API request is received, just select the top 10 entries from the event_counts table and returns them as JSON. That’s it.

Why Use an API?

You might wonder why we use an API instead of querying the database directly from Streamlit. Here are a few reasons:

- Decoupling: By separating the data access layer from the presentation layer, you can easily swap out or upgrade components without affecting the entire system.

- Scalability: An API can handle multiple clients and can be scaled independently of the Streamlit app.

- Reusability: Other applications or services can use the same API to access the data.

Actually, while we’re on the subject of APIs, it’s about time for a digression on why all this back end stuff is good to know in the first place.

An intro to Quix Streams — the library that powers the streaming data layer

I know I said I wasn’t going to talk too much about the streaming data layer, but I want to quickly show you how it works, because it’s really not as complicated as you might think.

It uses one Python library — Quix Streams — to produce to Redpanda (our Kafka stand-in), consume from it, then do our aggregations. If you know Pandas, you’ll quickly get the hang of it, because it uses the concept of “streaming data frames” to manipulate data.

Here are some code snippets that demonstrate the basics of Quix Streams.

Connecting to Kafka (or any other Kafka-compatible message broker) and initializing data source and destination.

# Initialize a connection by providing a broker address

app = Application(broker_address="localhost:19092") # This is a basic example, are many other optional arguments

# Define a topic to read from and/or to produce to

input_topic = app.topic("raw_data")

output_topic = app.topic("processed_data")

# turn the incoming data into a Streaming Dataframe

sdf = app.dataframe(input_topic)

All of the services in the streaming data layer (Streaming Data Producer, Aggregation service, and the Postgres Writer) use these basic conventions to interact with Redpanda.

The aggregation service uses the following code to manipulate the data on-the-fly.

sdf = app.dataframe(input_topic)

# Get just the "actor" data out of the larger JSON message and use it as the new streaming dataframe

sdf = sdf.apply(

lambda data: {

"displayname": data['actor']['display_login'],

"id": data['actor']['id']

}

)

# Group (aka "Re-key") the streaming data by displayname so we can count the events

sdf = sdf.group_by("displayname")

# Counts the number of events by displayname

def count_messages(value: dict, state: State):

current_total = state.get('event_count', default=0)

current_total += 1

state.set('event_count', current_total)

return current_total

# Adds the message key (displayname) to the message body too (not that necessary, it's just for convenience)

def add_key_to_payload(value, key, timestamp, headers):

value['displayname'] = key

return value

# Start manipulating the streaming dataframe

sdf["event_count"] = sdf.apply(count_messages, stateful=True) # Apply the count function and initialize a state store (acts as like mini database that lets us track the counts per displayname), then store the results in an "event_count" column

sdf = sdf[["event_count"]] # Cut down our streaming dataframe to be JUST the event_count column

sdf = sdf.apply(add_key_to_payload, metadata=True) # Add the message key "displayname" as a column so that its easier to see what user each event count belongs to.

sdf = sdf.filter(lambda row: row['displayname'] not in ['github-actions', 'direwolf-github', 'dependabot']) # Filter out what looks like bot accounts from the list of displaynames

sdf = sdf.update(lambda row: print(f"Received row: {row}")) # Print each row so that we can see what we're going to send to the downstream topic

# Produce our processed streaming dataframe to the downstream topic "event_counts"

sdf = sdf.to_topic(output_topic)

As you can see, it’s very similar to manipulating data in Pandas, it’s just that it’s data on-the-move, and we’re interacting with topics rather than databases or CSV files.

Running the Python files outside of Docker

With Docker, we’ve simplified the setup process, so you can see how the pipeline works straight away. But you can also tinker with the Python files outside of Docker.

In fact, I’ve included a stripped down docker-compose file ‘docker-compose-rp-pg.yaml’ with just the non-Python services included (it’s simpler to keep running the Repanda broker and the PostgreSQL DB in Docker).

That way, you can easily run Redpanda and Postgres while you tinker with the Python files.

docker-compose down

To continue working with the Python files outside of Docker:

- Create a fresh virtual environment.

- Install the requirements (this requirements file is at the root of the tutorial repo: *

pip install -r requirements.txt

- If your containers from the previous steps are still running, take them down with:.

docker-compose down

- Start the Redpanda and Postgres servers by running the “stripped down” docker compose file instead:

docker-compose -f docker-compose-rp-pg.yaml up

Now you’re ready to experiment with the Python files and run the code directly in an IDE such as PyCharm.

The next challenge

Here’s your next challenge. Why not update the services to create a real-time “trending repos” report by counting the most active repos in a 30-min time window?

You can use the Quix Streams Windowed Aggregations as a reference. After all, who wants to see the trending repos just for a whole day? Attention spans are getting shorter -and the world is going real-time — we need minute-by-minute updates! Life just feels more exciting when the numbers change before our eyes.

As a reminder, you can find all the code files in this repo: https://github.com/quixio/template-streamlit-rt-githubdash

Now, go forth and impress your colleagues with amazing real-time dashboards!

PS: If you run into trouble, feel free to drop me a line in the Quix Community slack channel and I’ll do my best to help.

Ce qui précède est le contenu détaillé de. pour plus d'informations, suivez d'autres articles connexes sur le site Web de PHP en chinois!