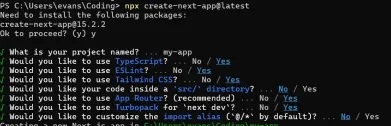

Every dev tools company and -team seems to assume that Junior Devs are familiar with these terms.

When I started to code, I saw them everywhere: Nuxt is an SSR framework, you can use Gatsby for SSG, and you can enable SPA mode if you set this or that flag in your next.config.js.

What the hell?

As a first step, here's a glossary – though it won't help you to understand the details:

- CSR = Client-Side Rendering

- SPA = Single Page Application

- SSR = Server-Side Rendering

- SSG = Static Site Generation

Next, let's shed some light into the dark.

Static Web Servers

Initially, a website was an HTML file you requested from a server.

Your browser would ask the server, "Hey, can you hand me that /about page?" and the server would respond with an about.html file. Your browser knew how to parse said file and rendered a beautiful website such as this one.

We call such a server a static web server. A developer wrote HTML and CSS (and maybe a bit of JS) by hand, saved it as a file, placed it into a folder, and the server delivered it upon request. There was no user-specific content, only general, static (unchanging) content accessible to everybody.

app.get('/about', async (_, res) => {

const file = fs.readFileSync('./about.html').toString();

res.set('Content-Type', 'text/html');

res.status(200).send(file);

})

Interactive Web Apps & Request-Specific Content

Static websites are, however, boring.

It's much more fun for a user if she can interact with the website. So developers made it possible: With a touch of JS, she could click on buttons, expand navigation bars, or filter her search results. The web became interactive.

This also meant that the /search-results.html page would contain different elements depending on what the user sent as search parameters.

So, the user would type into the search bar, hit Enter, and send a request with his search parameters to the server. Next, the server would grab the search results from a database, convert them into valid HTML, and create a complete /search-results.html file. The user received the resulting file as a response.

(To simplify creating request-specific HTML, developers invented HTML templating languages, such as Handlebars.)

app.get('/search-results', async (req, res) => {

const searchParams = req.query.q;

const results = await search(searchParams);

let htmlList = '

- ';

for (const result of results) {

htmlList += `

- ${result.title} `; } htmlList += '

A short detour about "rendering"

For the longest time, I found the term rendering highly confusing.

In its original meaning, rendering describes the computer creating a human-processable image. In video games, for example, rendering refers to the process of creating, say, 60 images per second, which the user could consume as an engaging 3D-experience. I wondered, already having heard about Server Side Rendering, how that could work — how could the server render images for the user to see?

But it turned out, and I realized this a bit too late, that "rendering" in the context of Server- or Client-Side Rendering means a different thing.

In the context of the browser, "rendering" keeps its original meaning. The browser does render an image for the user to see (the website). To do so, it needs a blueprint of what the final result should look like. This blueprint comes in the form of HTML and CSS files. The browser will interpret those files and derive from it a model representation, the Document Object Model (DOM), which it can then render and manipulate.

Let's map this to buildings and architecture so we can understand it a bit better: There's a blueprint of a house (HTML & CSS), the architect turns it into a small-scale physical model on his desk (the DOM) so that he can manipulate it, and when everybody agrees on the result, construction workers look at the model and "render" it into an actual building (the image the user sees).

When we talk about "rendering" in the context of the Server, however, we talk about creating, as opposed to parsing, HTML and CSS files. This is done first so the browser can receive the files to interpret.

Moving on to Client-Side Rendering, when we talk about "rendering", we mean manipulating the DOM (the model that the browser creates by interpreting the HTML & CSS files). The browser then converts the DOM into a human-visible image.

Client-Side Rendering & Single Page Applications (SPAs)

With the rise of platforms like Facebook, developers needed more and faster interactivity.

Processing a button-click in an interactive web app took time — the HTML file had to be created, it had to be sent over the network, and the user's browser had to render it.

All that hassle while the browser could already manipulate the website without requesting anything from the server. It just needed the proper instructions — in the form of JavaScript.

So that's where devs placed their chips.

Large JavaScript files were written and sent to the users. If the user clicked on a button, the browser would insert an HTML component; if the user clicked a "show more" button below a post, the text would be expanded — without fetching anything.

<meta charset="UTF-8">

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1.0">

<title>Document</title>

<div id="root"></div>

<script>

document.addEventListener('DOMContentLoaded', () => {

const root = document.getElementById('root');

root.innerHTML = `

<h1>Home

<button>About

`;

const btn = document.querySelector('button');

btn.addEventListener('click', () => {

root.innerHTML = `

<h1>About

`;

});

});

</script>

Though the code snippet suggests the opposite, developers didn't write vanilla JavaScript.

Ginormous web apps like Facebook had so much interactivity and duplicate components (such as the infamous Like-button) that writing plain JS became cumbersome. Developers needed tools that made it simpler to deal with all the rendering, so around 2010, frameworks like Ember.js, Backbone.js, and Angular.js were born.

Of them, Angular.js was the one that brought Single Page Applications (SPAs) into the mainstream.

An SPA is the same as Client-Side Rendering, but it is taken a step further. The conventional page navigation, where a click on a link would fetch and render another HTML document, was taken over by JavaScript. A click on a link would now fire a JS function that replaced the page's contents with other, already preloaded content.

For this to work properly, devs needed to bypass existing browser mechanisms.

For example, if you click on a

Devs invented all kinds of hacks to bypass this and other mechanisms, but discussing those hacks is outside the scope of this post.

Server-Side Rendering

So what were the issues with that approach?

SEO and Performance.

First, if you look closely at the above HTML file, you'll barely see any content in the

tags (except for the script). The content was stored in JS and only rendered once the browser executed the <script>. Hence, Google's robots had a hard time guessing what the page's content was about — in fact, they couldn't guess anything. <p>The site couldn't be indexed and thus wouldn't rank highly on Google. <p>Second, since the browser would only send a single request to the server and then continue to render the SPA on its own, all content that could ever be rendered had to be delivered with the initial request. With large web apps, this could easily surpass a couple megabytes, which slowed down the page load significantly. Amazon conducted a study that concluded businesses would lose 1% of revenue with every 100ms in added page load time, so that was a huge no-no for most companies. <p>In short, developers needed to create HTML files on the server again. <p>But they couldn't circle back to templating-languages and request-specific content — by now, everybody was writing React, and they loved the component-driven approach. Wasn't there a way to write React and render it on the server? Of course! With the advent of Node.js, developers were already writing JS on the backend, and the road to full-stack frameworks such as Next.js or Nuxt was paved. <p>Those frameworks render React (or Vue, Svelte...) on the server. Basically, React turned into a templating language such as Handlebars.<br> <pre class="brush:php;toolbar:false">// List.tsx import React from "react" export const List = (props: { results: { title: string }[] }) => ( <ul> {props.results.map((r) => ( <ListElement title={r.title} /> ))} ) export const ListElement = (props: { title: string }) => ( <li>{props.title} ) // server.ts app.get("/search-results", async (req, res) => { const searchParams = req.query.q const results = await search(searchParams) const fullPage = renderToString( React.createElement(List, { results }) ) res.set("Content-Type", "text/html") res.status(200).send(fullPage) }) <p>(Note: the only difference to the "Request-Specific Content" approach is that we're now using modern frontend frameworks to write our HTML.) <h2> Static Site Generation <p>Great, so our pages were indexable and fast again. <p>However, some sites weren't as fast as they <em>could be. <p>If the content didn't change (like the page of a blog post), why should the server newly fetch and build the HTML for every user visiting the page? That seemed wasteful. Wouldn't it be enough to build the HTML once and reuse it whenever somebody requested it? <p>That approach is called static site generation. <p>In contrast to the original static web server approach, where developers manually wrote and stored HTML files on the server, here, the HTML files were <em>generated: <p>Non-technical people wrote content and uploaded images in a CMS (Content Management System, such as WordPress or Sanity). Developers wrote React components, used the CMS's API, and executed a <em>build script that fetched the data for every page and built the HTML file according to the outlined blueprint. The finished file was then stored on the server, ready to be delivered upon a user's request. <p>Developers could then re-trigger the build script to create new files when new content became available. <h2> The new kid on the block: Server Components <p>As of August 2024, React Server Components (RSCs) – though still marked as experimental – are all the rage. <p>The basic idea is this: Before RSCs, a React Component first had to be delivered to the client. There, it would render and, if it needed to fetch data, send another request to the server; it had to wait for the response and re-render. This is wasteful. RSCs make it possible to both fetch the data and render the component on the server. Only the finished, isolated HTML component is sent to the client, and there merged with the existing HTML – the rest of the page is left as is. <p>The result is a much better performance: less back-and-forth between the server, fewer kilobytes over the network, and less re-rendering. <p>Plus, you can await your data right in your React Code, making it much simpler to write. <p>But, as usual when new features are added to existing frameworks, RSCs make React much more complex. You must constantly consider whether you need a component on the server or the client; caching layers are involved; interactivity is impossible with RSCs – tl;dr, the waters are still muddy. <p>As a counter-movement, developers who are fed up with the front-end complexity have started to write and favor simple frameworks, such as HTMX. </script>The above is the detailed content of The Junior Developer&#s Complete Guide to SSR, SSG and SPA. For more information, please follow other related articles on the PHP Chinese website!

Python vs. JavaScript: The Learning Curve and Ease of UseApr 16, 2025 am 12:12 AM

Python vs. JavaScript: The Learning Curve and Ease of UseApr 16, 2025 am 12:12 AMPython is more suitable for beginners, with a smooth learning curve and concise syntax; JavaScript is suitable for front-end development, with a steep learning curve and flexible syntax. 1. Python syntax is intuitive and suitable for data science and back-end development. 2. JavaScript is flexible and widely used in front-end and server-side programming.

Python vs. JavaScript: Community, Libraries, and ResourcesApr 15, 2025 am 12:16 AM

Python vs. JavaScript: Community, Libraries, and ResourcesApr 15, 2025 am 12:16 AMPython and JavaScript have their own advantages and disadvantages in terms of community, libraries and resources. 1) The Python community is friendly and suitable for beginners, but the front-end development resources are not as rich as JavaScript. 2) Python is powerful in data science and machine learning libraries, while JavaScript is better in front-end development libraries and frameworks. 3) Both have rich learning resources, but Python is suitable for starting with official documents, while JavaScript is better with MDNWebDocs. The choice should be based on project needs and personal interests.

From C/C to JavaScript: How It All WorksApr 14, 2025 am 12:05 AM

From C/C to JavaScript: How It All WorksApr 14, 2025 am 12:05 AMThe shift from C/C to JavaScript requires adapting to dynamic typing, garbage collection and asynchronous programming. 1) C/C is a statically typed language that requires manual memory management, while JavaScript is dynamically typed and garbage collection is automatically processed. 2) C/C needs to be compiled into machine code, while JavaScript is an interpreted language. 3) JavaScript introduces concepts such as closures, prototype chains and Promise, which enhances flexibility and asynchronous programming capabilities.

JavaScript Engines: Comparing ImplementationsApr 13, 2025 am 12:05 AM

JavaScript Engines: Comparing ImplementationsApr 13, 2025 am 12:05 AMDifferent JavaScript engines have different effects when parsing and executing JavaScript code, because the implementation principles and optimization strategies of each engine differ. 1. Lexical analysis: convert source code into lexical unit. 2. Grammar analysis: Generate an abstract syntax tree. 3. Optimization and compilation: Generate machine code through the JIT compiler. 4. Execute: Run the machine code. V8 engine optimizes through instant compilation and hidden class, SpiderMonkey uses a type inference system, resulting in different performance performance on the same code.

Beyond the Browser: JavaScript in the Real WorldApr 12, 2025 am 12:06 AM

Beyond the Browser: JavaScript in the Real WorldApr 12, 2025 am 12:06 AMJavaScript's applications in the real world include server-side programming, mobile application development and Internet of Things control: 1. Server-side programming is realized through Node.js, suitable for high concurrent request processing. 2. Mobile application development is carried out through ReactNative and supports cross-platform deployment. 3. Used for IoT device control through Johnny-Five library, suitable for hardware interaction.

Building a Multi-Tenant SaaS Application with Next.js (Backend Integration)Apr 11, 2025 am 08:23 AM

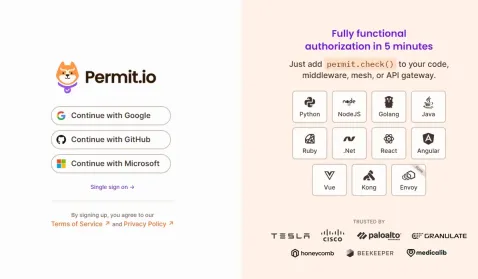

Building a Multi-Tenant SaaS Application with Next.js (Backend Integration)Apr 11, 2025 am 08:23 AMI built a functional multi-tenant SaaS application (an EdTech app) with your everyday tech tool and you can do the same. First, what’s a multi-tenant SaaS application? Multi-tenant SaaS applications let you serve multiple customers from a sing

How to Build a Multi-Tenant SaaS Application with Next.js (Frontend Integration)Apr 11, 2025 am 08:22 AM

How to Build a Multi-Tenant SaaS Application with Next.js (Frontend Integration)Apr 11, 2025 am 08:22 AMThis article demonstrates frontend integration with a backend secured by Permit, building a functional EdTech SaaS application using Next.js. The frontend fetches user permissions to control UI visibility and ensures API requests adhere to role-base

JavaScript: Exploring the Versatility of a Web LanguageApr 11, 2025 am 12:01 AM

JavaScript: Exploring the Versatility of a Web LanguageApr 11, 2025 am 12:01 AMJavaScript is the core language of modern web development and is widely used for its diversity and flexibility. 1) Front-end development: build dynamic web pages and single-page applications through DOM operations and modern frameworks (such as React, Vue.js, Angular). 2) Server-side development: Node.js uses a non-blocking I/O model to handle high concurrency and real-time applications. 3) Mobile and desktop application development: cross-platform development is realized through ReactNative and Electron to improve development efficiency.

Hot AI Tools

Undresser.AI Undress

AI-powered app for creating realistic nude photos

AI Clothes Remover

Online AI tool for removing clothes from photos.

Undress AI Tool

Undress images for free

Clothoff.io

AI clothes remover

AI Hentai Generator

Generate AI Hentai for free.

Hot Article

Hot Tools

MantisBT

Mantis is an easy-to-deploy web-based defect tracking tool designed to aid in product defect tracking. It requires PHP, MySQL and a web server. Check out our demo and hosting services.

SAP NetWeaver Server Adapter for Eclipse

Integrate Eclipse with SAP NetWeaver application server.

VSCode Windows 64-bit Download

A free and powerful IDE editor launched by Microsoft

SublimeText3 English version

Recommended: Win version, supports code prompts!

ZendStudio 13.5.1 Mac

Powerful PHP integrated development environment